Starting a Fund – One Year In

Lessons from the first year of launching a hedge fund

Welcome to Bristlemoon Capital! We have written previously on FICO, UNH, META, GRND, HEM SS, MELI, U, APP, PDD, IBKR, PAR, AER, PINS, BROS, MTCH, CPRT, RH, EYE, and TTD. If you haven’t subscribed, you can join 5,008 others who enjoy our deep dives and investment insights here:

Free subscribers will only receive a partial preview of our reports. The remainder of our reports, which contain the deeper analysis, are reserved for paid subscribers. Consider becoming a paid subscriber for full access to our reports.

Bristlemoon readers can also enjoy a free trial of the Tegus expert call library via this link.

Australian wholesale investors looking to invest in the Bristlemoon Global Fund can do so via this link.

Lessons from launching a hedge fund

Last year, George Hadjia discussed the journey of launching Bristlemoon Capital, following an X (Twitter) post that garnered interest from the FinTwit community. One year following the launch of the Fund, George details further lessons from building Bristlemoon.

It is worth opening this post with some of the more memorable comments I received from people before launching Bristlemoon Capital.

"How are you going to raise any money?"

"If you don't partner with someone [a capital partner] I can tell you right now it's going to be a miserable failure".

"You should go to another fund first and get a track record".

"You're not smart enough to work at a hedge fund".

Starting a fund requires grit. Most people will be encouraging and supportive when you divulge your fund launch plans. Others won’t be. Having full conviction in what you’re trying to build from the outset, and the tenacity to see it through, is critical. Without a clear vision, any negative comments along the way might dissuade you from taking the fund launch plunge.

At the risk of stating the obvious, the odds of successfully scaling up a fund are low. An investment fund as a business requires a lot of AUM to become self-funding. With this in mind, it maybe sounds foolhardy, even crazy, to have launched Bristlemoon Capital last year with no major investor commitments, instead bootstrapping the business from my own savings.

Launching Bristlemoon has been the most challenging, but also the most fulfilling thing I’ve ever done. In this post I will detail some lessons I’ve picked up in the first year since launch that may be relevant for those contemplating starting their own fund, or starting a business in general. Launching any sort of business can be a difficult process – it helps to have a good reason for starting a fund, and to know what you’re signing up for.

Why start a fund?

Many investment analysts, whether secretly or overtly, harbor ambitions to one day start their own fund. I was no exception. During an interview for a hedge fund role in 2015, I was asked “where do you see yourself in 10 years?” My response, somewhat naively and perhaps far too candidly, was “I want to be running my own fund”.

To best frame the rationale for starting your own fund, it’s instructive to think through when it makes sense to not start a fund.

There are broadly two reasons for staying at an existing fund as an analyst: 1) you are learning a lot from those around you; and/or 2) you are being paid well for your contributions.

If you are achieving both, and are given research autonomy by your portfolio manager, then this can make for a satisfying job. If you are achieving neither, then the impetus to leave and start your own fund will be higher.

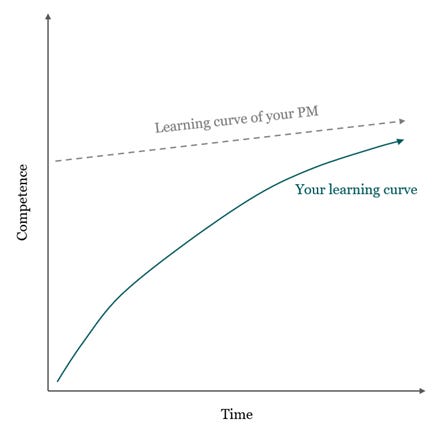

While it makes sense to hone your craft at an established fund early in your career, the problem is that your learning curve as an investment analyst will inevitably begin to flatten. In other words, the rate at which you are accumulating new investing knowledge from those around you will naturally slow down over time. This dynamic is especially noticeable as you get more senior in your career, given you have already built up a base of expertise.

As the competence gap between yourself and your portfolio manager narrows, the potential for pushback on your portfolio manager’s thoughts and ideas increases. This pushback often serves as the fuel for wanting to start your own fund. It can become more difficult to maintain job satisfaction if your stock and business suggestions are being overruled by a portfolio manager you increasingly view as an equal.

Another factor that feeds into the fund launch calculus is the way that a fund’s economics are split, with your superiors typically taking a larger slice of the pie.

Starting a fund may seem like a neat way to kill two birds with one stone, enabling you to: 1) capture full decision-making autonomy; and 2) benefit from a greater share of the fund’s economics.

Sure, these are possible benefits from starting your own fund. But you are giving something up for them; don’t forget that.

When you are working at a fund as an employee, you will only capture a mere sliver of the value you are generating. But in return, you enjoy a level of stability and safety. You will receive a salary, knowing precisely how much will be deposited in your bank account each month. Many of the strategic and operational decisions will be borne by somebody else, enabling you to spend the majority of your time researching stocks. You will likely receive mentorship and there will often be a clear, pre-defined path for career progression.

Launching a fund means abandoning these benefits that stem from being an employee, and not an owner. You will be out on the open seas and it’s incumbent upon you to navigate the route forward when managing your own fund.

You have to acknowledge and be prepared for everything that comes with the fund launch route. It is far more than just picking stocks and reaping the associated rewards. You will be running a business – the operational, compliance, regulatory, tax, and marketing burdens will need to be considered. You will be running a team as the fund scales, and you must be equipped to deal with a multitude of people issues. You are responsible for building your fund’s brand, letting the world know that you’re open for business and are worth investing in.

Much of your mental bandwidth will be consumed by the venture, so you must accept that simply shutting off is not really an option. There is no convenient “off switch” when you have been entrusted with managing the capital of others.

If all of this sounds like an acceptable trade-off, then it’s worth thinking through the various ways in which you can approach a fund launch.

The different ways to start a fund

The number of fund launch options available to you will heavily depend on your personal circumstances. The key considerations are as follows:

Your experience and whether you have a marketable track record;

The amount of personal capital you have saved;

Your relationships with individuals and organizations that would be comfortable backing you; and

Your risk appetite.

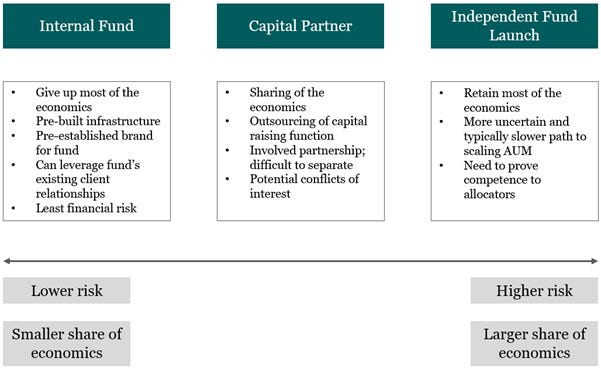

We can plot the different fund launch archetypes along a spectrum. Notably there’s often an inverse relationship between the level of risk taken in the fund launch approach and the level of fund economics you will capture (but not always).

Launching an internal fund within an established fund manager

This route is the least risky from a financial sense. You will likely be underwritten with a salary, and the fund manager bears the expenses of the fund. The trade off is that you will keep a much smaller share of the fees – often just some portion of the performance fee for the capital you have discretion over. While these arrangements vary, at best you might be able to capture half of the performance fee.

This is potentially still very lucrative, particularly if the fund has a good reputation and established distribution capabilities to scale up your internal fund.

Partnering with a capital partner

In this arrangement, you will ostensibly be running your own fund and will be able to build a brand. You will split the economics with the capital provider on the basis that they will do the heavy lifting on raising money for the fund. This can work very well. It can also be problematic to the extent that often these capital partners are representing multiple investment managers, with potential conflicts of interest to the extent there are other managers in the same asset class with a similar strategy that are also being marketed to allocators.

Furthermore, you won’t have control over the distribution personnel, which are interfacing with end clients and representing your brand. This is fine if the capital partner has professional and competent personnel. It can be an enormous distraction to the extent that they don’t, and any decision to separate from a capital partner could be a messy undertaking given the sharing of economics.

An alternative is to launch the fund independently, build up a track record, and then retain the option to partner with a capital partner if the fund’s AUM does not reach sufficient scale.

Launching a fund independently

Within this option there are a variety of flavors. Launching out of a high-pedigree, name-brand fund with your own track record will translate into a very different AUM scaling path compared to launching from a no-name fund with no track record. While success in the latter scenario is not impossible, and there are cases of under-the-radar managers launching with $1-2 million of AUM with no pedigree and no track record, who then scale to hundreds of millions of dollars of AUM in a matter of years, it is a much harder path.

The trick is properly appreciating how the AUM ramp up might look for the type of fund launch you choose and then appropriately budgeting for that. A common reason emerging managers fail is that they run short of personal capital before they can get enough traction. In order for your fund to be able to scale, you need the financial runway to stay in the game long enough to prove yourself to investors.

It’s critical to be realistic about how long it takes to properly scale a fund. It is an almost certainty that it will take longer than what you think.

The advice I was given was to haircut your AUM launch expectations by 90%. This was precisely our experience – to the dollar, in fact. Virtually every fund manager we have spoken to launched with significantly less capital than what they were expecting. That’s just how it goes. But it does make the journey harder, and it reinforces the need to be very sure that you do indeed want to start a fund.

The personal side to starting a fund

Much of the fund launch decision will hinge on your personal circumstances. Here are some questions you should consider:

Do you have the personal capital to give yourself sufficient runway to build a track record and raise capital? At this point I have gone more than two years without a salary. It is an uncomfortable adjustment, but a necessary part of the journey of building something great.

Are you willing to drastically lower your personal cash burn in order to extend this runway? This means significantly curtailing discretionary expenditures. For some, the associated hit to one’s lifestyle might be wholly unpalatable, particularly if a spouse is not okay with making the same sacrifice.

Do you have a spouse, and are they onboard with you taking on this monumental challenge? Absent this support, the demands of running the fund, in terms of time, energy, and money, could put strain on your relationship.

Do you have relationships with wealthy individuals who will give you money to manage? The reality is that no matter how good of an investor you are, if you don’t have a network of people that trust you enough to invest with you, then you will struggle to convert your investing acumen into a viable business. There is a sales component to building a funds management business that can’t be ignored. Be honest with yourself around your ability to network and build relationships with wealthy individuals. Any shortcomings here will make the scaling process much more difficult.

Launching a fund too early can be detrimental. If you are too young, allocators (most of which are likely to be older than you) will not take you seriously.

However, launching a fund too late can also be problematic. One’s personal cash burn tends to increase over time due to mortgages, additional dependents such as a spouse and children, schooling fees, etc.

There is likely a sweet spot for launching a fund where you have sufficient experience, but do not have a personal life that has become too financially encumbered. You will need to factor all of this into the level of personal capital you have when starting the fund.

Launching a fund is launching a business

When you launch a fund, it can be difficult to retain your investing purism. For example, if you were managing only your personal capital, you might invest with a certain desired approach. However, when running a fund your capital is co-mingled with the capital of external investors. Their expectations and goals might not perfectly align with yours. In fact, it is almost certain that their expectations and goals won’t perfectly align with yours. However, it is the fees from these clients that will underpin your business, so their expectations and goals must be duly reflected in the fund’s strategy.

At the end of the day, a funds management business isn't so much managing a portfolio as it is creating an investment product that is saleable and well-received by the target market. This requires product market fit. So, the investment strategy must be carefully designed so as to be attractive to potential investors. It is sometimes a delicate balance in reconciling how you might want to manage the portfolio, and how capital allocators want the portfolio managed.

If you are too much of a purist, you will trade AUM scalability for job satisfaction. If you are too commercial and design the product so that it has maximum appeal to the target market, you risk running a strategy that is poorly-aligned with how you want to manage capital, and in the worst case, is impaired in its ability to generate good returns.

Some of the fund parameters that are important to consider are when structuring an investment strategy are as follows:

Gross and net exposure ranges and limits for a long/short fund

Maximum cash weighting for a long only fund

Maximum position size

Sector concentration limits

Sector or geographic specialization

Quality bias (or not)

Portfolio turnover

Level of volatility

Fee structure

Be very careful with how you craft your fund’s strategy. Often there is a push and pull between retaining enough flexibility in your investment mandate to generate good investment returns and having a narrow enough focus to carve out a niche that makes you stand out to allocators.

Many allocators will already have investments in a variety of funds – if yours doesn’t stand out, it might be hard to get a look in. This is where a fund with a more narrowly defined mandate can help open doors with allocators. Specialization in a niche with a compelling argument for why that niche is ripe with investment opportunities will resonate more with some capital providers than simply saying you’re a good stock picker and will find great opportunities wherever they present.

For example, a fund that only invests in SMID cap technology stocks in Southeast Asia will probably generate more initial interest from allocators than a fund that has an open investment mandate. The lack of constraints in the latter fund makes it harder for allocators to mentally pigeonhole that strategy. This simply makes it more difficult for an allocator to determine how that fund will blend with the remainder of their manager investments.

The other consideration with a niche strategy is that there will be periods where the market will be favorable for that strategy. Performance will be good, making it easier to get traction with capital allocators. However, there will also be periods when the market environment for that targeted niche becomes unattractive, perhaps even hostile. It then becomes increasingly hard both to make money and attract investor interest.

By committing to a more narrowly focused strategy, particularly if investors are allocating to that strategy to get a certain exposure, you are then locked into that approach. Launching a fund with a narrow mandate means you are basically rolling the dice, hoping for a market environment that is kind to the investing approach you’ve adopted. This is clearly problematic to the extent that you launch into an environment that is punishing stocks in your targeted domain. This can create genuine business risk.

The timing of when you start a fund matters, an incredible amount actually. You could be a savvy tech investor, but if you had launched a U.S. tech fund at the beginning of 2022, there were few places to hide in that sector from the carnage that ensued over the course of that year.

The narrower the approach, the more you will need luck on your side in the early years of the fund to help you build a solid track record. Absent this, and if bad luck strikes early in the fund’s life, then it is likely to elongate the AUM scaling process as it will take time to get the fund’s performance back on track.

Launching solo or with a business partner/team

I launched Bristlemoon as a solo operator. My thinking was to get the business up-and-running and build a track record with my own capital in a structure that could later onboard external capital. It was a leap of faith, and frankly I didn’t know for sure whether other investors would enter the fund at such a nascent stage.

Thankfully I was able to secure capital from some early backers, and our AUM has grown healthily since then, allowing me to bring on my close friend and former colleague, Daniel Wu, as a business partner.

Launching a fund as a solo operator has its benefits. You have total autonomy. You also get to intimately understand the various aspects of your own business (versus outsourcing the various functions to a team). The problem, however, is it is more difficult to scale as a solo operator, and unfettered autonomy doesn’t always translate into the best decisions.

Numerous investors we’ve spoken to also expressed more comfort in having more than one person running the fund.

Bringing Daniel into Bristlemoon has been a gamechanger for the business. We are able to share the workload and he’s served as a great sounding board to pressure test ideas. All of this translates into greater rigor in the decision making process.

Managing a portfolio with someone else requires a huge amount of trust and knowing how to calibrate the other person’s judgment. For example, Daniel saying “I think this stock is good” is probably the equivalent of another investor banging the table and saying “this is a generational buying opportunity where we need to back up the truck”.

People express their views and opinions differently; having familiarity with how that person communicates their stock calls is an important part of a solid investment partnership. Often there’s no substitute to achieve this level of understanding outside of having countless detailed investing discussions and knowing that person for a long period of time to understand the quirks of their personality.

Before starting Bristlemoon I spoke to many who'd started their own investment firms, but had later decided to wind down their funds. I found the stories of why some of those firms had subsequently shuttered to be illuminating. Many cited an irreconcilable dispute with their co-founder that led to them parting ways. An investment partnership is akin to a marriage; choose your partner wisely.

Prior to Bristlemoon, I had known Daniel for 14 years, and we had been talking about launching a fund together for a decade. We were housemates in Sydney and New York, and worked together for years. Becoming business partners was a pretty straightforward decision for both of us.

But even with a shared history, it is still vital to figure out roles and responsibilities, as well as economics before you set out. Figure out exactly who will do what, and formalize a shareholders agreement before you set out on the journey. The absolute last thing you want to be doing is figuring out how to share the pie mid-journey. You particularly don’t want to be negotiating the economic split on an ongoing basis. That’s a recipe for contention and disagreement. Just agree on how the economics will be divided between yourselves and then stick to it.

Markers of legitimacy / building credibility

Step into the shoes of a prospective client who’s contemplating investing money in your fund. Even if they’ve met you multiple times, there’s not a lot from the outside they have to go off to get comfort – after all, most funds are a bit of a black box. Maybe they can see your website and research you’ve written. Regardless, there’s often a trust and credibility gap that typically needs to be bridged.

For this reason, many prospective investors rely on heuristics, typically seeking out markers of legitimacy. This manifests in prospective investors asking us similar questions:

How big is the team?

How much AUM do you have? (Rarely do investors want to be the first to invest in a new fund. AUM has a high signaling function and more of it gives investors confidence that others have confidence in you)

Where’s your office? (Working from home, while perfectly fine, is far less comforting to some investors than having a city address)

Where do you live? (I get this question all the time, believe it or not. Prospective investors, rightly or wrongly, draw comfort if you live in a good suburb rather than a rough part of town. It shouldn’t matter one iota to your ability to generate investment outperformance, but it hints at the mental shortcuts prospective investors take to try to assess whether you’re credible.).

To the extent that you can tick these boxes, you give a prospective investor fewer reasons to say no to investing in your fund. In fact, every strategic business decision you make should be in service of reducing the number of reasons a prospective investor might be inclined to say no. Many of these frictions reduce over time. Others will depend on structuring decisions that are made at the outset of the fund launch journey.

No one cares about your fund more than you

The funds management space is crowded and competitive, with limited vectors across which you can truly differentiate yourself. There is no shortage of fund managers saying the same things: “We take a long-term view, buying quality stocks that are mispriced”. This certainly makes it more difficult to stand out, and without something to make you stand out, you will likely be reduced to a commodity product in the eyes of an allocator.

The truth is no one will care about your fund more than you do. The wealthy individuals you will be pitching to have their own priorities, and investing in your fund is probably not super high on their list. They are probably not thinking about how critical it is to promptly invest in your fund when they’re out vacationing in Saint-Tropez. Now, this doesn’t mean that they’re not interested in your fund whatsoever, but it does mean that there’s typically a healthy dose of persistence needed to chase up prospective investors to build those relationships. It usually requires a balance between being politely persistent, but not so persistent that you become a pest.

I hope you enjoyed these thoughts and reflections. It’s an honor to get to share these learnings and I hope they’re of use for anyone who has contemplated starting their own fund. If these thoughts resonated with you, or if you have been on a similar journey, I’d love to hear from you and can be reached at info@bristlemoon.com.

Disclaimer / Disclosures

The information contained in this article is not investment advice and is intended only for wholesale investors. All posts by Bristlemoon Capital are for informational purposes only. This article has been prepared without taking into account your particular circumstances, nor your investment objectives and needs. This article does not constitute personal investment advice and you should not rely on it as such. This document does not contain all of the information that may be required to evaluate an investment in any of the securities featured in the document. We recommend that you obtain independent financial advice before you make investment decisions.

Forward-looking statements are based on current information available to the author, expectations, estimates, projections and assumptions as to future matters. Forward-looking statements are subject to risks, uncertainties and other known and unknown factors and variables, which may affect the accuracy of any forward-looking statement. No guarantee is made in relation to future performance, results or other events.

We make no representation and give no warranties regarding the accuracy, reliability, completeness or suitability of the information contained in this document. To the maximum extent permitted by law, we do not have any liability for any loss or damage suffered or incurred by any person in connection with this document.

Bristlemoon Capital Pty Ltd (ABN: 22 668 652 926) is an Australian Financial Services Licensee (AFSL Number: 552045).

George Hadjia and Daniel Wu are associated with Bristlemoon Capital Pty Ltd. Bristlemoon Capital may invest in securities featured in this newsletter from time to time.

I really enjoyed this one. I've been debating for some time about quitting my job and starting my own fund. I currently run a partnership (without fees) with a group of friends. I will make sure to read this periodically. And I wish you nothing but success on your journey.

Great read! Thanks for sharing your experience