PDD Holdings (PDD) – Amazon’s Greatest Threat?

A deep dive on the high-growth, e-commerce powerhouse

Welcome to Bristlemoon Capital! We have written previously on APP, IBKR, PAR, AER, PINS, BROS, MTCH, CPRT, RH, EYE, TTD, and META. If you haven’t subscribed, you can join 3,221 others who enjoy our deep dives and investment insights here:

Free subscribers will only receive a partial preview of our reports. The remainder of our reports, which contain the deeper analysis, are reserved for paid subscribers. Consider becoming a paid subscriber for full access to our reports.

Bristlemoon readers can also enjoy a free trial of the Tegus expert call library via this link.

Introduction

Pinduoduo is a one-of-a-kind company. It was founded in 2015. The following year, Pinduoduo generated RMB 505 million in revenue (roughly $72 million). Not bad! However, fast-forward to 2023 and the company generated close to RMB 250 billion of revenue (circa $35 billion), a more than 490x increase in revenue over just seven years.

How many businesses can you think of that generated $35 billion in revenue in their seventh year of operation? It’s insane. This led to Pinduoduo becoming the fastest company in history to achieve $100 billion of market capitalization, reaching this milestone in just five years. For comparison, it took Amazon 18 years to go from founding to a $100 billion market capitalization.

Readers may be familiar with the e-commerce platform called Temu, which is also owned by PDD. Temu was founded in July 2022. In just over two years, it became the world’s second most visited e-commerce website, sitting behind only amazon.com[1]. The platform is now expected to generate $50 billion of gross merchandise value (GMV) in FY24. This is unheard of growth: from zero to tens of billions of GMV in a little over two years is truly incredible and has never before happened in the world of retail.

So what got us interested in PDD? Well, for starters, it is growing its profits at 156% year-over-year yet trades on a cash-adjusted FY25E P/E of just 6x. We will look at how PDD makes money across its Pinduoduo and Temu businesses, dive into the unit economics of these platforms, and then look at the growth prospects for PDD.

Table of Contents

Business Overview

First-party or third-party?

The Pinduoduo platform

Team purchase model allows rapid scaling

Gamification of e-commerce

Temu

Fully managed and semi-managed models

The de minimis provision

Consumer-to-Manufacturer (C2M) model

How does PDD make money?

Is China Uninvestable?

Is PDD Uninvestable?

A Short Business History

Temu – a Counter-Positioning Story

High merchant overlap with appetite for a new sales channel

Temu products are cheaper than on Amazon

Amazon’s ability to compete is hamstrung by its current model

Financials

Unit economics

Valuation

Business Overview

PDD Holdings Inc. (PDD) is a multinational e-commerce company that owns two key e-commerce platforms: Pinduoduo and Temu. Pinduoduo is the domestic e-commerce platform (i.e., Chinese merchants selling within China) while Temu is the global platform, allowing mostly Chinese merchants to sell their wares into around 80 countries[2].

First-party or third-party?

For any e-commerce platform, there is a question of whether it is a first-party (1P) or third-party (3P) retailing model. The distinction between the two comes down to whether there’s a transfer of ownership of inventory (and thus whether this inventory is held on the balance sheet). In a 1P model, the e-commerce platform purchases the inventory from the merchant, takes ownership of said inventory, and then assumes the risk of selling that inventory to consumers on its platform. Aside from an early incarnation of the platform, this is not what Pinduoduo or Temu are doing (we will dig into the various Temu models later in the report). Rather, Pinduoduo and Temu are third-party e-commerce platforms: they act as marketplaces, simply connecting buyers with merchants.

On the Pinduoduo platform, merchants are responsible for fulfilling the order and will select a third-party logistics provider to arrange for the delivery of the products to buyers.

Source: Bristlemoon Capital; FT

The Pinduoduo platform

Pinduoduo was started in 2015. It is an e-commerce platform that offers a broad range of products including agricultural produce, apparel, shoes, bags, food and beverages, consumer electronics and appliances, furniture, cosmetics, and many more. In 2020, the company launched Duo Duo Grocery, a next-day grocery pickup service that is integrated within the Pinduoduo mobile app. Duo Duo Grocery connects local farmers and distributors directly to consumers.

Pinduoduo is not like conventional e-commerce companies which rely on intent-driven shopping and a solitary shopping experience. Pinduoduo’s platform uses feed-based shopping that’s personalized to a user’s preferences, allowing them to serendipitously discover items they may not have known they wanted. User demand preferences are then collated by Pinduoduo and fed back to merchants, directing future production quantities for goods.

Source: Company filings

One of the key differences between Pinduoduo and any Western e-commerce platform is the highly social shopping experience of Pinduoduo, supported by the team purchase concept.

Team purchase model allows rapid scaling

Pinduoduo utilizes a “team purchase” model. Under this model, buyers are able to form groups on Pinduoduo and then receive discounts by purchasing items as a group.

Merchants will decide two prices for an item: 1) the price for an individual purchasing that good; and 2) the discounted price for a team purchase. For example, buyers who want to buy paper towels can band together to form a group on Pinduoduo and receive the cheaper price by buying in bulk. The team needs to be formed within 24 hours to complete the order. Buyers are still able to buy items as individuals (as opposed to a team purchase) but will lose access to the lower price if they make the purchase without forming a group (virtually all Pinduoduo’s transactions are completed via the team purchase option).

Source: Company filings

During Pinduoduo’s early years, the size of the groups was relatively large (often greater than 10 people were required to form a group). As the platform has scaled, the team size requirement has gotten smaller.

For readers who love a bargain, this team purchase model might sound familiar. Groupon, which started back in 2008, offered discounts to groups of people who bought a product. Groupon, however, struggles to make money and has lost around 98% of its value since its IPO. However, at its core, Groupon is a deal site that happens to have collective buying functionality. Businesses use Groupon to clear one-off products or services that aren’t selling, offering steep discounts. Pinduoduo, on the other hand, is selling everyday goods (in contrast to the impulse purchase activity on Groupon) with group buying at its core. The models are fundamentally different, and this is reflected in the very different financial profiles of these two businesses.

The team purchase model was an ingenious way for Pinduoduo to scale its user base. Users have a direct financial incentive to recruit other users into their groups – that is, they can access a discount if their group hits the requisite number of buyers. This saw users sharing product information on social networks such as WeChat, and inviting their friends and family to form shopping teams where they could all enjoy more attractive purchase prices under the “team purchase” option.

WeChat was critical in making it possible for Pinduoduo to scale up. For those unfamiliar with WeChat, it is the super app through which Chinese netizens conduct their lives. Pinduoduo users would post items that they’re buying on their WeChat, recruiting people to join their purchase groups for items they’d already be purchasing anyway such as fruit and household essentials. For example, the number one product on Pinduoduo was facial tissues[3]. This helped lower the friction for new users using Pinduoduo: these were low average selling price items (i.e., less risk to the user if the platform was a scam) that could be purchased at a discount, and they were items that the user would be buying anyway. By leveraging WeChat, Pinduoduo was tapping into the concept of social proof, whereby legitimacy was derived from others using the platform.

The close integration Pinduoduo enjoyed with WeChat was supported by the fact that Tencent, the owner of WeChat, held a 16.9% stake in Pinduoduo (Tencent still has a 14.1% stake in PDD as of February 29, 2024). Tencent was thus happy to allow Pinduoduo to build on top of its ecosystem. We love businesses that were only able to achieve scale due to irreplicable circumstances, and PDD certainly ticks this box. No other firm would have a chance of reaching Pinduoduo’s scale in the same compressed time frame absent WeChat’s assistance. It is close to impossible now for any other firm to use WeChat in the same way to scale an e-commerce platform; users know simply to go to Pinduoduo for team purchases.

Pinduoduo’s team purchase model created a self-reinforcing virtuous cycle that led to unparalleled growth in users.

Source: Company filings

The company is a network effect business, connecting buyers with merchants. More buyers on the platform attracts a greater number of merchants who benefit from the greater sales volume potential. As the number of merchants increases, PDD is able to offer even more competitive prices, attracting more buyers, and thus creating a positive feedback loop.

Gamification of e-commerce

The company has been described as a mix between Costco and Disneyland; PDD has crafted a gamified shopping experience, drawing in consumers looking for value-for-money items. Essentially, PDD makes digital shopping social and fun in a way that drives strong user engagement and viral user growth.

In order to make the in-app experience fun and social, Pinduoduo employs a number of mechanisms borrowed from the world of online gaming. These tactics are aimed at stimulating user engagement, retention, and promoting viral (i.e., cheap) customer acquisition. It is worth exploring these tactics in a bit of detail as they are integral to PDD’s model and help us understand what makes the company special, and how PDD achieved such meteoric growth.

Free products

One example of a growth hack used by PDD is where a user can receive free products if they get enough new users to follow the Pinduoduo official account or install the Pinduoduo app. For example, one promotion in 2018 was that if a user could generate nine new app installs, they’d receive a 1.3 kilogram bag of Three Squirrels nuts. This was fantastic growth marketing, with each new user acquired via this free product promotion costing Pinduoduo just RMB 3, or around $0.40[4].

Price Chop

Then there’s what’s called “Price Chop”, where users can share affiliate links with their friends in order to get items for free. For example, a user will click the Price Chop icon and then select the good that they want to get for free. Pinduoduo generates an invite that the user can then distribute to their contacts on WeChat. The user then has 24 hours to get the price down to zero, and a timer commences in order to build urgency. This is achieved by getting friends to click on the custom link (it is not necessary for them to purchase the item); every click of the link will reduce the price of the item.

If the user fails to get the price of the item down to zero (i.e., they didn’t get enough people to click the link), they will then forfeit the discount and must start from scratch. The level of discounts asymptote as the user gets closer to chopping the price down to zero, meaning that as the user approaches zero, incremental users clicking the link will generate smaller and smaller discounts[5]. Users have to work even harder to secure the final few discounts necessary to get the item for free. The difficulty of the Price Chop is customized based on the user (e.g., new or low engagement users will have an easier Price Chop difficulty) and the item (i.e., more expensive items are harder to “chop”[6]). While users are getting free items, the Price Chop drives an enormous amount of activity on the platform that keeps existing users highly engaged, while drawing in new users via social networks.

Source: Tech In Asia

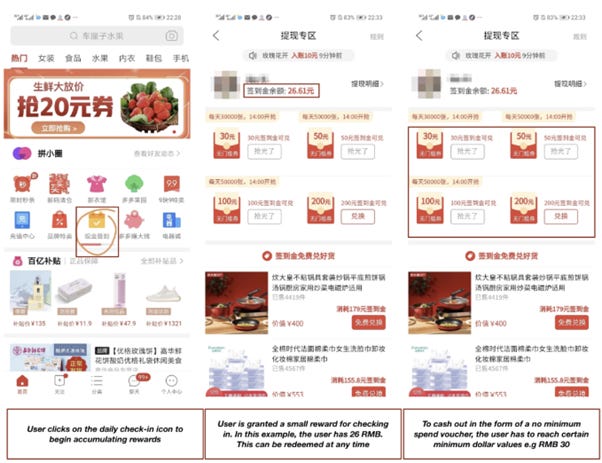

Daily check-in

Another example of gamification within the app is the daily check-in feature. On the home page of the Pinduoduo app, users see a check-in icon that they can click to receive rewards, incentivizing daily usage of the app.

Source: Y Combinator

There’s a button within the app that allows users to convert their rewards to cash. While users can transfer these digital rewards to real money in WeChat Pay or the Pinduoduo Wallet, they can only do so in RMB 100 increments. What this means is that if you have, for example, RMB 96 worth of rewards, you must go back into the app to earn more rewards before you are able to convert any of those digital tokens to real money.

Periodically users will get an “acceleration card” whereby the rate at which they accumulate redeemable points doubles for the next five minutes, prompting users to go back into the app and engage with earning rewards. Pinduoduo also displays a leaderboard of users who earned the most money from inviting friends to the app, creating competition amongst users to invite new users to Pinduoduo and progress up the leaderboard.

There are a slew of other features, including the following:

Lotteries, whereby users will pay a small entry fee and must invite friends to the lottery within a specified time frame for the lottery to be active. For example, if an iPhone worth RMB 5,000 is the lottery prize, then each user might contribute RMB 1 as a deposit for a chance at winning the item. If 5,000 users join the lottery, it then becomes active, and a winner will be drawn. If the lottery fails to attain 5,000 users, then those that entered the lottery get their RMB 1 deposit back. This lottery is euphemistically dubbed “One Yuan Treasure Hunt”, and it is somewhat surprising to us that this model has been allowed, given that gambling is illegal in China.

Mini Games. Pinduoduo hosts in-app games such as Duo Duo Orchard, helping increase the daily time spent on the platform. Think of it like Pinduoduo’s version of Farmville but where users instead earn rewards in the form of physical goods, such as a box of oranges[7]. Users receive water droplets from shopping on Pinduoduo which they can use to water their virtual trees. They can also share these water droplets with friends, making mini games such as Duo Duo Orchard inherently social. Once a user’s tree reaches a certain level, they receive an actual box of fruit.

Source: Y Combinator

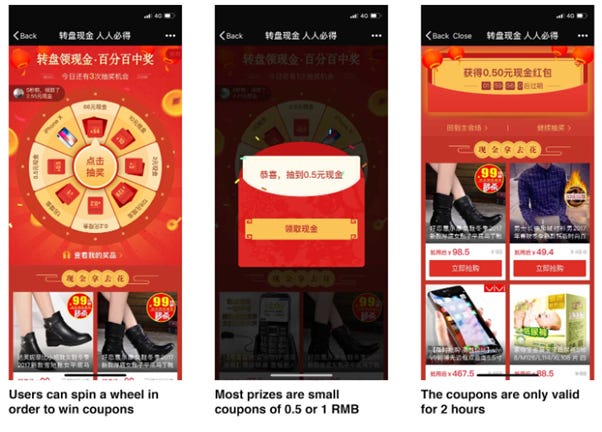

Coupons which have a very short duration: typically only two hours. Users can spin a roulette wheel and win prizes, usually coupons with a small value of say 0.5 to 1 RMB. Users must use these coupons quickly before they expire, driving purchase activity.

Source: Tech In Asia

It should be clear now that PDD is the master of gamifying shopping. Notably, the company has ported many of these gamification tactics over to Temu, which is scaling rapidly.

These gamification methods turbocharged PDD’s user growth. Back in 1Q17, Pinduoduo had around 68 million annual active buyers, 15 million of which were monthly active users (MAUs) (i.e., would log in to the Pinduoduo app monthly). This equated to 22% of users who had purchased an item on Pinduoduo being monthly active users. In 1Q22, the last period in which these numbers were reported, Pinduoduo had almost 882 million annual active buyers, 85% of were monthly active users (i.e., 751 million MAUs)[8].

What is clear from these numbers is a phenomenal level of growth: Pinduoduo 50x’d its MAUs in five short years. To contextualize Pinduoduo’s growth, it took the company just four years to hit 500 million active buyers, compared to around 15 years for Alibaba[9]. In fact, Pinduoduo’s circa 882 million annual active buyers in 1Q22 eclipsed the 828 million China Retail Marketplace annual active buyers reported by Chinese e-commerce juggernaut Alibaba in the same period. Think about how insane that is. It’s the equivalent of an investor looking at Amazon’s U.S. business in 2019, and then today in 2024 having an out-of-nowhere competitor achieve a larger annual active buyer base. It’s unfathomable.

Temu

Temu was launched in September 2022. It became the most downloaded shopping app in the U.S. just two weeks after launching and has maintained the top spot every day for two years[10]. According to Marketplace Pulse, the Temu app ranks number one in most of the roughly 80 countries in which it operates[11]. The platform offers a selection of merchandise in categories such as apparel, electronic appliances, household goods, tools, sports and fitness, and pet supplies. These goods are sold at bargain basement prices. Temu is likely to sell an estimated $50 billion worth of goods this year, with an estimated $18 billion of that GMV coming from the U.S. (i.e., a 36% share of GMV).

Temu has a strict AI-driven price verification system. It can analyze the amount and quality of materials used in a merchant’s product as a way to estimate the cost. Prices of products on Temu are also compared against other platforms to ensure low prices. If merchants on other platforms are found to have lower prices, Temu will penalize the uncompetitive merchant on its platform via a drop in traffic. This ensures that only the most efficient, lowest-priced merchants thrive on Temu.

The way Temu manages its platform is enormously data driven. What to supply, how to price it, how to allocate user traffic to merchants – it is decided in a data-intensive manner, looking at prices, product rankings, sell-through rates, user reviews, et cetera. This again helps drive lower prices by prioritizing the most efficient merchants in a way that would not be possible in a traditional marketplace model where merchants were operating individually with greater autonomy.

Notably, Temu is a separate platform from Pinduoduo. Temu is the global e-commerce platform where mostly Chinese merchants can sell goods to countries outside of China at bargain prices. Pinduoduo is a different platform comprised of Chinese merchants selling into the Chinese market. The two platforms, however, have significant overlap in their merchant bases (UBS channel checks suggest that the overlap between Temu and domestic PDD merchants is as high as 50%).

Temu is a marketplace that connects buyers with merchants, using a global network of logistics vendors and fulfilment partners to facilitate the delivery of purchased goods. Temu’s unique model blends the advantage of having control over product pricing from a 1P model (i.e., Temu sets the price for goods on its platform) with no inventory risk under a 3P model (merchants ship the products, with no transfer of product ownership to Temu).

Below is an example of what the Temu user experience looks like.

Source: Temu

First-time users are drawn in with coupons that provide large discounts on a range of items.

Source: Temu

In just one and a half years, Temu MAUs comprised 22% of global e-commerce platform MAUs in April 2024, according to Sensor Tower data.

Source: Sensor Tower; UBS

Temu has also aggressively expanded its geographic footprint, with the platform accessible in around 80 countries as of late 2024.

Source: Goldman Sachs Investment Research; Company data

Fully managed and semi-managed models

When Temu was launched in September 2022, it used what is called a fully managed model. Under this fully managed model, merchants supply their goods, but Temu takes care of everything else (hence the name “fully managed”). Temu is responsible for handling pricing and promotions, warehousing, international logistics and refunds/returns. The genesis of this model addresses the merchant pain point of having to handle cross-border logistics when selling into international markets. For example, a Chinese merchant selling on Temu under its fully managed model will supply its products, but Temu will organize for those goods to be shipped internationally.

In March 2024, Temu launched a semi-managed model. Under the semi-managed model, merchants are responsible for arranging their own logistics, and handling operations and aftersales customer care (i.e., refunds and returns). So, what typically happens for a Chinese merchant selling to a U.S. consumer is as follows: they will ship their product to a U.S. warehouse (as opposed to using air freight to transport goods under the fully managed model) and then fulfil the order from the U.S. warehouse.

N.b.: the semi-managed model is referred to by various other names including semi-entrusted and semi-consignment.

The below diagram illustrates the differences between Temu’s fully managed and semi-managed models.

Source: UBS

Why did Temu introduce the semi-managed model? There are a number of benefits:

The semi-managed model allows Temu to supply U.S. demand with inventory that’s already in the U.S. This helps Temu expand into higher average selling price (ASP) categories where direct air mail isn’t economic or feasible (e.g., furniture or large household goods). According to merchant feedback collated by Bernstein, the higher average order values (AOVs) under the semi-managed model have allowed Temu to offer prices that are 20-30% below Amazon, while still allowing Temu merchants to achieve attractive margins under this new model (with these margins in some cases approaching those that are achieved on Amazon).

The semi-managed model allows for shorter delivery times due to products being delivered from U.S. warehouses. The semi-managed model allows Temu to offer 3-5 day delivery times, compared to 9-12 days under the fully-managed model.

This model also reduces geopolitical risk around Temu’s reliance on the de minimis provision for fully managed transactions (we will explore this further below). Under the semi-managed model, the goods are already in U.S. warehouses and merchants would have already paid the required import tariffs.

UBS’s channel checks suggest that merchant overlap between Temu’s semi-managed model and Amazon is as high as 70-80%. Many local merchants view Temu as an attractive channel for inventory destocking, with UBS estimating that this accounts for 20-30% of their volume.

In the table below, Goldman Sachs has provided a useful comparison of Temu’s fully managed and semi-managed models with AliExpress and Amazon.

Source: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research; Company data

The de minimis provision

The de minimis provision refers to Section 321(a)(2)(C) of the U.S. Tariff Act of 1930, which allows goods with a fair retail value of under $800 to enter the U.S. without having to pay the typical fees, tax, and duty associated with importation[12]. Qualifying imports also don’t need to fill out the extensive paperwork that’s otherwise required when a good is imported from overseas. In short, the de minimis provision allows foreign merchants to get their goods into the U.S. for cheaper, and with less hassle.

Why is this provision worth mentioning? Well, the spirit and intention of the Act was to benefit American tourists who wanted to send goods back home to the U.S., reducing the administrative headaches of filing customs paperwork for sending these low value items to the U.S. However, the provision is now being relied on by offshore e-commerce platforms such as Temu to skirt U.S. taxes and duties.

The threshold for the de minimis provision was actually raised in 2016 from $200 to the current $800, as a way to reduce costs and facilitate trade. But this increase in the threshold had unintended consequences, one of which was allowing Chinese merchants to dramatically expand their volumes of merchandise imported into the U.S. without paying duties.

It does seem logical that the U.S. would want to crack down on the de minimis provision, as it advantages foreign retailers. Brick-and-mortar retailers based in the U.S., in contrast, typically bulk import their goods into the country, paying any necessary duties and taxes. Amazon merchants that use Fulfillment by Amazon are also required to ship their products from U.S. warehouses, at which point they will have already paid duties on those imported goods.

According to statistics released by the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agency, the U.S. is on track to import around 1.5 billion de minimis packages in 2024, compared to roughly 500 million in 2019. Notably, Temu and Shein comprise nearly half of the de minimis shipments that entered the U.S. from China[13], and more than 30% of the total de minimis shipments into the U.S., creating risks in the event that this loophole is closed[14].

The problem for Temu is that the U.S. appears to now be cracking down on the de minimis customs exemption. Back in May 2024 the U.S. CBP agency suspended several customs brokers from participating in what’s called the Entry Type 86 program, which speeds up low-valued packages clearing U.S. customs[15]. Furthermore, on September 13, 2024, the Biden-Harris administration announced it was cracking down on the de minimis provision, using executive authority to exclude from the de minimis exemption all shipments containing products subject to existing tariffs. The White House also called on Congress to pass legislation to reform the de minimis exemption.

There are a few things we would note in relation to the de minimis loophole potentially being closed:

Merchant checks by Macquarie pointed to Temu’s average order value in the U.S. being in the $35-40 range, which compares to approximately $70-75 for Shein. Notably, both of these average order values are demonstrably below the $800 de minimis threshold. A reduction in the de minimis threshold would likely be ineffective in curtailing Temu’s volumes, making tariffs a more likely option. However, the implementation of this would be difficult.

The U.S. processes 4 million de minimis packages per day. The administrative burden of auditing the origin of each package would be unwieldy and likely a non-starter in a government apparatus that’s likely to be downsizing under the Trump administration.

In substance, Temu is exporting Chinese production overcapacity. Due to the ultra-low prices, Temu’s exports to the U.S. are deflationary, and have come at a key time when the U.S. is trying to tame stubborn inflation. Slapping tariffs on these imports, which in all likelihood would be borne by the end consumer, is counter to efforts within the U.S. to curb inflation (although we doubt that this would stop Trump from following through with his tariff threats if he so desired).

The result of there being risks to the de minimis provision has seen Temu pivot hard to the semi-managed model, where merchants will bear the cost of any tariffs when arranging for their goods to enter the U.S. According to Marketplace Pulse, 20% of Temu’s U.S. sales in July 2024 were coming from local warehouses in the U.S[16]. This is a dramatic shift, given that this number was zero at the start of 2024. It also shows remarkable execution, given that local sellers only started getting onboarded to Temu in March 2024[17].

This de minimis provision discussion makes it seem like Temu is only able to achieve cheap prices for goods on its platform by exploiting this loophole. We do not believe that this is the case, and this is due to the company’s unique consumer-to-manufacturer (C2M) model, which cuts out supply chain intermediaries and passes the resulting savings on to consumers.

Consumer-to-Manufacturer (C2M) model

PDD has pioneered a unique approach to retailing that it refers to as Consumer-to-Manufacturer (C2M). This name might sound confusing. After all, aren’t the manufacturers selling goods to the consumer? If we think about traditional retailing models, retailers bulk order goods from suppliers and then figure out ways to sell those goods to consumers. In other words, retailers order inventory from suppliers upfront, before any sales are made. Supply precedes demand.

PDD takes a different, somewhat brilliant approach. Given the hundreds of millions of users browsing goods on its platform, the company uses this data to predict consumer preferences and then inform merchant production decisions. In this sense, PDD shifts the retail model from supply-driven to demand-driven. This helps guarantee demand for merchants and reduces the risk that they overproduce and are left with goods that they’ll struggle to sell.

PDD Founder Colin Huang wrote the following about the C2M model in a blog post (which has since been deleted):

“Assuming we are able to make the front-end consumers a little more patient and more willing to coordinate with others and give up some impulse of “I want it now”, then we have the opportunity to use people’s recommendations and relationships and the similarity of their interests to group people. This process consolidates every individual’s personalized needs to certain planned needs with some time buffer. This consolidation may not be as centralized as Wal-Mart’s half-year bulk orders, but it will be enough to get a production line to run economically. So we have the opportunity to split a large Wal-Mart order into 50 small batch orders. The back-end production will be able to get rid of dependence on Wal-Mart. Instead of the original production planning model of being authorized manufacturers, dozens of capable manufacturers can compete for these 50 smaller batch orders categorized by different group needs”

The C2M model also improves the value-for-money proposition for consumers by cutting out middlemen. By pooling consumer demand and enabling suppliers to sell directly to consumers, rather than through an inefficient, multi-layered supply chain, PDD is able to sell goods at prices that other retailers are unable to compete with. This large scale, aggregated demand also allows suppliers to tap into economies of scale that they would otherwise forgo if selling in a decentralized way, and thus allows them to more effectively compete with larger, scaled competitors.

Source: Company filings

The below comments from Founder Colin Huang provide further color around PDD’s retail strategy, which he dubs “new e-commerce”:

“This is in the DNA of “new e-commerce.” Pinduoduo was born in the mobile Internet era, bypassing the PC era’s search-based online shopping model which placed products first. “New ecommerce” no longer treats each individual merely as traffic nor does it simply take wholesale distribution of such traffic as its business model. Instead, “new e-commerce” tries to understand the human touch behind each click; it tries to aggregate similar needs through analyzing the connections and trust amongst people. Only when we wholeheartedly serve and respect people, can we harness the collective power of the people and transform long-cycled scattered demand into short-cycled aggregated demand. This introduces the possibility of on demand customized production, improves supply chain efficiency, and returns value to their creators – the everyday workers.” – Colin Huang, 2019 Letter to Shareholders

How does PDD make money?

PDD has two revenue segments: 1) Online marketing services and others; and 2) Transaction services.

The Online marketing services segment is an advertising business. PDD matches product listings – that is, an ad of a merchant’s product – with user search or browser results. For example, a user might be browsing their feed or searching for a product in the search bar within the Pinduoduo app. Pinduoduo then algorithmically populates the user’s feed with relevant products. The merchant is charged based on the number of impressions and clicks received for their product listings.

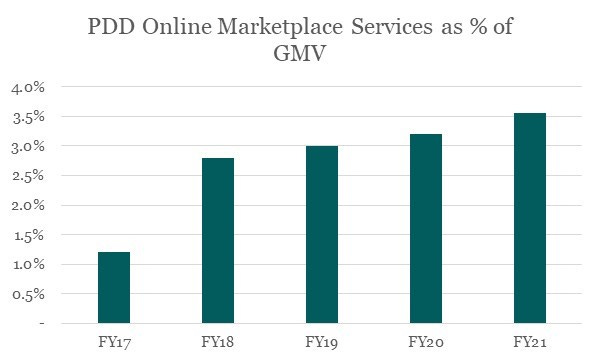

Note that merchants prepay for this service, creating free float via a negative cash conversion cycle. Conceptually, we can think of PDD earning a take rate based on a percentage of GMV, driven by advertising dollars merchants must spend to achieve a certain level of GMV. For the periods in which we have GMV data, PDD’s take rate more than tripled between FY17 to FY21 to 3.6% (which is still a small amount relative to other platforms). Bernstein estimates that PDD’s take rate reached 4.2% in FY23.

Source: Bristlemoon Capital; Company filings

The second revenue stream is Transaction services, which includes the provision of fulfillment services to merchants, and related fees for sales of products completed on PDD’s platforms. Revenues from Temu and Duoduo Grocery are captured within Transaction services. Notably, PDD does not take control of the products provided by merchants at any point in time during a transaction.

Rather than monetizing via an advertising-driven take rate, Temu earns a markup on top of the price provided by suppliers. What this means is that Duoduo Grocery and Temu record a much higher percentage of GMV as revenue compared to the main Pinduoduo platform (Bernstein estimates 10-15% of GMV for Duoduo Grocery and around 35% of GMV for Temu, with 40% under the fully managed model, and low double digits under the semi-managed model).

The following content is for paid subscribers only. Thank you to all our paid subscribers!