Fair Isaac Corporation (FICO) – Pricing Power Impaired?

Exploring the industry standard for US consumer credit risk

Welcome to Bristlemoon Capital! We have written previously on UNH, META, GRND, HEM SS, MELI, U, APP, PDD, IBKR, PAR, AER, PINS, BROS, MTCH, CPRT, RH, EYE, and TTD. If you haven’t subscribed, you can join 4,917 others who enjoy our deep dives and investment insights here:

Free subscribers will only receive a partial preview of our reports. The remainder of our reports, which contain the deeper analysis, are reserved for paid subscribers. Consider becoming a paid subscriber for full access to our reports.

Bristlemoon readers can also enjoy a free trial of the Tegus expert call library via this link.

Australian wholesale investors looking to invest in the Bristlemoon Global Fund can do so via this link.

Introduction

Investors love businesses with pricing power. The ability to raise prices without losing customers is one of the clearest indications of a business moat. Fair Isaac Corporation (Nasdaq: FICO) is one of the more notable examples of a public company exerting its pricing power in recent times. The company dramatically raised the prices of its eponymous credit score in a very short span of time.

For some context, the company didn’t raise its credit score royalty rates in real terms for nearly 30 years. But following an intense process of contract renegotiation that permitted FICO to begin raising prices, which we’ll explore, the price of a FICO Score went from around 50-60 cents in 2022 to $4.95 per score in 2025. In other words, FICO raised its prices by 800% in just three years! Clearly, FICO has been making up for lost time on the pricing front.

The company argues that there remains a demonstrable price-to-value gap with its FICO Score that it is seeking to narrow (i.e., via further price increases). Regulators, however, have taken notice, and have sought to break FICO’s monopoly by making changes that attempt to foster competition in the scores market. The key question is the extent to which these changes will erode FICO’s monopoly as well as the company’s ability to continue its heady price increases.

This has caused investors to fret over whether FICO still has pricing power. This tends to be problematic when a company’s stock trades at over 60x earnings, as FICO did earlier this year, and where the future growth is almost wholly reliant on price increases. Consequently, the regulatory rumblings have brought about an enormous destruction of value in FICO’s equity, with the share price declining by 45% from the all-time high of c.$2,380 in November 2024, to c.$1,300 in August 2025.

Source: Bloomberg; Bristlemoon Capital

This report is intended to serve as a primer so that you can understand how FICO’s business works, from the nuances of its Scores business, its complicated relationship with the credit bureaus, as well as some financial analysis to better understand the economics of FICO’s growth story. We also unpack the key debates surrounding the stock, and analyze the potential ways in which FICO’s business might develop in the future.

Key Takeaways

FICO is not only a monopolist in the credit score market, but its credit score is used as the industry standard for consumer credit risk in the U.S. The company has aggressively increased prices, raising them by 800% over the last three years. This growth has led to 95% incremental operating margins for the Scores business, and operating margins that are near 90%.

The FICO Score is incredibly entrenched in the US mortgage ecosystem, and it is infused into multiple systems, workflows and regulatory requirements across the point of loan origination, as well as the secondary market securitization value chain. The FICO Score very much is not just a number referenced by lenders, but is integral to the plumbing of the U.S. mortgage system in a way that makes the score very sticky.

FICO is used at different stages of a mortgage application, and we estimate that there are roughly 10-12 credit pulls in a typical mortgage application, resulting in $49.50 to $59.40 of royalties for FICO. FICO’s royalties comprise a small part of total mortgage closing costs – in the vicinity of 90 basis points for a typical mortgage loan. FICO, however, has attracted regulatory scrutiny from the FHFA, despite the fact that the bulk of incremental credit report inflation can be attributed to the credit bureaus and other third parties layering on fees and marking up the cost of the FICO Score when a tri-merge credit report is generated.

FICO has a somewhat complicated relationship with the credit bureaus – one that we would categorize as “frenemies”. While the three major credit bureaus compete with FICO via their VantageScore JV, the bureaus also make more revenue from marking up the FICO Score than what FICO makes from its scores. Both FICO and the credit bureaus are well-incentivized for FICO to continue its aggressive pricing campaign, and we believe there is an exceedingly low chance that any traction from VantageScore would result in a race to the bottom on prices.

The securitization market, in particular the standardization of the to-be-announced market where more than 90% of agency MBS are traded, acts as a gating factor on VantageScore getting traction. Heterogenous loan pools – that is, those that use both FICO and VantageScore – are harder to price and we believe that MBS investors will demand a discount for loan pools scored with VantageScore. There is also the risk of loan putbacks that create a disincentive for lenders to deliver loans to the GSEs with an alternate score such as VantageScore, in the case that those loans default and the GSEs force the lender to buyback the loan at par.

We estimate that for every basis point of VantageScore risk premium over FICO, a borrower will end up paying over $900 more over the life of a 30 year, $400,000 mortgage underwritten using VantageScore. We estimate that the value of the savings over the term of a mortgage are potentially 100x greater than the $50 in royalties FICO might receive in a dual borrower mortgage origination.

Table of Contents

Business Overview

Software – a brief mention

Scores – the key value driver for FICO

The FICO Score is the Industry Standard

Creating an industry standard

Moving away from an industry standard

Are there examples of an industry standard being displaced?

Business History

FICO’s Special Price Increases

The Real Cost of Price Increases

The CRAs have contributed more to credit report cost inflation than FICO

Regulatory Woes

Increased Competition in the Credit Score Market?

FICO 10 T vs VantageScore 4.0

VantageScore is more inclusive?

FICO’s Relationship with the Credit Bureaus

The quirks of the VantageScore JV

Do the credit bureaus make more from a FICO Score than from VantageScore?

The GSEs and the Securitization Market

FICO Score the industry standard for mortgage securitization

The To-Be-Announced (TBA) Market

Risk of loan putbacks

Why are lenders complaining about the FICO Score if the cost is passed through to consumers?

What is the Value of the FICO Score?

Concluding Comments and Valuation

Business Overview

FICO’s business is comprised of two segments:

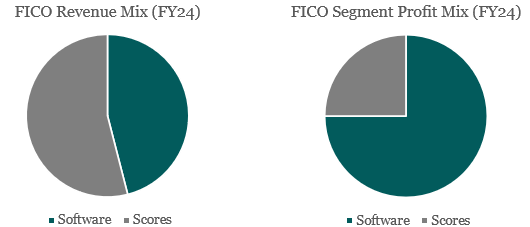

Scores (FY24: 54% of revenues and 75% of operating income)

Software (FY24: 46% of revenues and 25% of operating income)

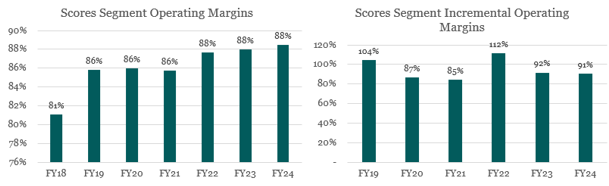

The Scores segment is the key value driver for FICO as a business. Not only does it comprise three-quarters of the company’s profits (it is incredibly high margin, with 88% segment operating margins in FY24), but it also contributes the bulk of incremental profit dollars, given that the Scores segment is growing relatively faster and at much higher incremental margins than the Software business (Scores revenues have come in at 95% incremental margins on average over the last six years).

Software – a brief mention

FICO’s Software business covers six categories: fraud detection, customer management, originations, financial crimes compliance, customer engagement and marketing. The company typically sells its software as multi-year subscriptions, with payments based on usage metrics such as the number of accounts, transactions, or decisioning use cases.

FICO’s Falcon Fraud Manager dominates the fraud detection market. It can determine whether a transaction is fraudulent or not in 15 milliseconds, and it protects two-thirds of credit card transactions worldwide. FICO TRIAD Customer Manager, which is a decision management software suite used by lenders to optimize and automate credit decisions, is similarly dominant in its market segment. We could spend pages talking about FICO’s Software business but it’s the Scores segment that is going to drive the value of the stock, so we will spend the remainder of the report on Scores. We would just lastly note that FICO management have expressed openness to one day selling the Software business, and the Software and Scores segments operate independently.

Scores – the key value driver for FICO

FICO is an applied analytics business, with the company best known for its flagship FICO Score product. The FICO Score – a three-digit number ranging between 300 and 850 – is the standard measure of consumer credit risk in the U.S. This metric is used by over 90% of the top U.S. lenders when making consumer lending decisions across mortgages, auto loans, credit cards, and other areas[1]. Typically, the higher your FICO Score, the lower your credit risk, and thus the greater the likelihood that lenders will write you a loan.

The FICO Score is used to rank-order individuals against a certain variable, such as the likelihood of making a credit payment on time. It utilizes five major factors in determining the score, weighting each of those factors based on predictive importance:

Payment history (35%)

Amounts owed (30%)

Length of credit history (15%)

New credit (10%)

Credit mix (10%)

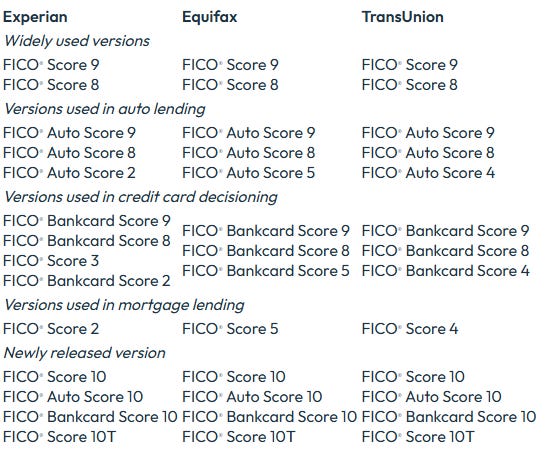

FICO uses predictive modelling to uncover patterns in historical data, which enables classifications about future credit outcomes to be represented by a single FICO Score number (although notably there are over 50 variations of FICO Score for various markets, including FICO periodically releasing new generations of FICO Scores which refine how the algorithm interprets credit bureau data, or incorporate the ability to process additional datasets).

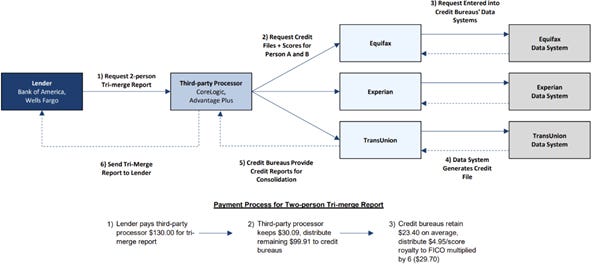

FICO is really a licensing business. The company has a set of intellectual property that is used in the underwriting process to assess credit risk. FICO licenses out this intellectual property to the three U.S. consumer reporting agencies (CRAs) – Experian, TransUnion, and Equifax – and in return receives royalties from the CRAs. It is worth noting that the three major credit bureaus mentioned above accounted for 45% of FICO’s revenues in FY24, and 84% of the company’s Scores revenue.

Below is a visual depiction of the process to generate a credit score:

Source: Jefferies

FICO is not actually the entity that produces the FICO Score. It is the CRAs that apply FICO’s proprietary analytic algorithms to their respective credit data in order to generate a FICO Score. The CRAs then sell the resulting FICO Score to lenders and other end-users (typically via resellers). In this sense, the credit bureaus act as distributors, and are an intermediary between FICO and the ultimate user of the scores product. Importantly, FICO doesn’t house or handle any of this sensitive consumer credit data.

The end users of FICO’s products are mainly financial institutions, with the company’s products being utilized by three-quarters of the 100 largest financial institutions in the U.S. It is then perhaps unsurprising that FICO’s largest market segment is financial services, comprising 92% of FY24 revenue.

The Scores business is further broken down into business-to-business (B2B) Scores (77% of total Scores revenue) and business-to-consumer Scores (23% of Scores revenue). Lastly, FICO is primarily concentrated in the Americas region, with this geography representing 84% of FY24 revenue.

The FICO Score is the Industry Standard

It is worth spending a moment to discuss what industry standards are, why it’s valuable to be an industry standard, and how FICO’s deep integration into the U.S. lending markets has made it the industry standard for assessing and monitoring credit risk.

An industry standard refers to a technical specification, practice, or product that is widely used across an industry as a baseline for compatibility, quality, and interoperability. Essentially, an industry standard is what joins different parties together in a way that allows them to unlock value.

In the context of FICO, credit data on a single borrower is not particularly useful. Data in isolation is simply far less valuable than datasets that have been joined together. If the credit data of millions of borrowers can be joined via a singular representation of credit risk, then that data becomes exponentially more valuable. This is what the FICO Score represents: a “join key” that links these millions of credit datasets in a way that unlocks value in the form of not only more predictive loan underwriting, but a common language for participants in the lending industry to communicate credit risk.

In a great article on Data-As-A-Service, Auren Hoffman made the following insightful observations[2]:

“One of the big ways that data becomes useful is when it is tied to other data. The more data can be joined, the more useful it is. The reason for this is simple: data is only as useful as the questions it can help answer. Joining, linking, and graphing datasets together allows one to ask more and different kinds of questions…the more join keys (and joined data sets) you can find, the more valuable those data become…As you keep joining data, the number of questions you can ask grows exponentially.”

There are two things to bear in mind for industry standards: 1) it is incredibly hard to make something an industry standard, and it often requires a unique set of goldilocks circumstances; and 2) once a market builds around an industry standard, it is enormously challenging to move off that industry standard.

Creating an industry standard

An industry standard can arise from voluntary consensus (e.g., agreement on a standard by an industry consortium), widespread market adoption (i.e., one company gets so much market share that it becomes the de facto standard), or it can be mandated by regulators.

In the case of FICO, it became the de facto standard due to widespread lender adoption. U.S. lending institutions adopted the FICO Score for two key reasons: 1) it allowed them to write better loans, given the FICO Score did a better job of predicting default risk than those banks’ internal methods at the time; and 2) a number of regulatory changes, such as the Equal Credit Opportunity Act in 1974, supercharged the adoption of the FICO Score, given that algorithmic credit scoring was an ideal way to assuage regulators that a given lending decision was not discriminatory.

The adoption of the FICO Score as the industry standard came from a set of irreplicable circumstances – namely being the first mover in creating an algorithmic scoring system at a period in time where regulatory changes made it highly convenient for lenders to adopt said scoring system.

Moving away from an industry standard

Shifting to a new industry standard is very difficult. It is a bit of a chicken-and-egg problem. Industry participants might be interested in utilizing a new standard but will be reluctant to adopt that new standard until others are already using it. So, this means that either a very large industry participant, or a group of participants need to switch to the new standard en masse to drag along the other players. In an industry as fragmented as that of lending in the U.S., we believe that there is an exceedingly low likelihood of the industry shifting away from the FICO Score. Industry standards, due to the immense switching costs when moving to a different system, often have significant longevity.

A good example of an industry standard is the QWERTY keyboard. It is a subpar arrangement of keys in terms of typing speed and ergonomics, yet it’s hard to imagine switching from this standard, given it’s the keyboard arrangement virtually everybody has become accustomed to, as well as how integrated it is into computer hardware. This is the power of industry standards: once they’re entrenched, they are really difficult to move away from. Regardless of any incremental ergonomic benefits from a redesigned keyboard, it would be a tall order to convince consumers to switch to a different keyboard design (e.g., Dvorak or Colemak) when virtually no one else is using those alternate designs. And because of these frictions consumers face when switching, keyboard manufacturers have very little incentive to push for change (particularly given they do not bear the cost of a slightly less ergonomic keyboard).

It's possible to map the value of an industry standard using Metcalfe’s Law. Metcalfe’s law states that the value of a network is proportional to the square of the number of connected users. In other words, the more industry participants that use the FICO Score as the industry standard, the more useful that standard becomes. This is particularly so when you have multiple types of industry participants all rely on the industry standard – in the case of the FICO Score, it is relied upon by borrowers, lenders, investors, and regulators.

The FICO Score is infused into multiple systems, workflows, and regulatory requirements across the point of loan origination, as well as the secondary market securitization value chain. The FICO Score very much is not just a number referenced by lenders, but is integral to the plumbing of the U.S. mortgage system in a way that makes the score very sticky. Below are a few ways in which FICO is integrated into the mortgage ecosystem:

Loan Origination Systems (LOS) – LOSs such as ICE’s Encompass and Black Knight’s Empower integrate with resellers to pull a tri-merge credit report (which includes a separate FICO Score from each of the three credit bureaus). The LOS then stores the middle FICO Score as the representative score for the borrower, and uses this score in loan eligibility calculations.

Automated Underwriting Systems (AUS) – Fannie Mae’s Desktop Underwriter (DU) and Freddie Mac’s Loan Product Advisor (LPA) require a FICO Score as an input. Without a FICO Score it is currently impossible to get GSE conforming loan approval.

Loan pricing engines – FICO is a key input into Loan Level Pricing Adjustments (LLPAs), with secondary desks explicitly bucketing pricing by FICO bands (e.g., 720-739, or 700-719). Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac publish LLPA grids (these are essentially rate sheets that determine basis points price hits (or credits) to the loan amount based on risk factors such as the FICO score, loan-to-value ratio, occupancy type, etc.) but it is the secondary desks within lenders that operationalize these LLPAs (we will dig into this and the role of GSEs later in the report). In this sense, the LLPA grids, which are based on the FICO Score, allow lenders during the origination phase of a mortgage to efficiently establish and adjust loan pricing based on the individual risk profile of the borrower.

Servicing and loan performance models – Mortgage servicers monitor borrower credit health post-origination by using FICO Scores. Both GSEs and mortgage servicers will rely on periodic FICO credit pulls to make updated assessments of delinquency and prepayment risk (which feeds into mortgage servicing rights (MSR) valuations and loss mitigation waterfalls).

Secondary market and MBS structuring – when GSEs package loans into mortgage backed securities (MBS), pool-level disclosures include the weighted average credit score. For decades that score has always been the FICO Score, and this continues to presently be the case. Credit risk transfer securities issued by Fannie and Freddie (i.e., CAS and STACR, respectively) explicitly reference FICO as the risk metric.

Regulatory capital and supervisory models – FHFA stress testing and GSE capital frameworks (e.g., ERCF) use loan-level FICO distributions as key drivers of expected default and loss models. Furthermore, banks holding MBS also bucket their capital requirements based on FICO-driven credit quality segments.

Private Mortgage Insurance (PMI) – the FICO Score is an integral part of PMI pricing models. It is what underpins insurance eligibility decisions as well as setting insurance premiums.

Other systems – there are a range of additional mortgage industry players that are reliant on FICO. For example, the Mortgage Industry Standards Maintenance Organization (MISMO), which is responsible for developing standards for exchanging information in the U.S. mortgage industry, has a FICO-centric data schema. Quality control and loan audit systems such as QC Ally use FICO thresholds for defect categorization. Servicing transfer data tapes (i.e., the loan-level dataset that the current servicer of a mortgage portfolio delivers to the new servicer when MSRs are sold or transferred) carry FICO fields.

If you can appreciate the challenge of moving away from the QWERTY keyboard in a scenario that involves only consumers and keyboard manufacturers, imagine trying to find ways for all of these disparate parties in the U.S. mortgage industry to make the changes necessary to support a second scoring method such as VantageScore. The problem becomes even more difficult when you consider that many of these industry participants have little incentive to make the investments necessary to support a second credit score beyond FICO.

The following quote from the Founding President and former CEO of VantageScore (via Tegus) is revealing:

“My first call on Fannie was in October of 2006. They had already tested us and said, "Will you outperform FICO on predictiveness?" I thought, "Well, this is going to be a slam dunk." Here we are 19 years later. I just think there's so much inertia.”

In other words, when VantageScore was introduced in 2006, it was believed that it would be able to encroach on FICO’s stronghold in the mortgage market. Almost two decades later and VantageScore’s impact has been negligible.

The truth is the mortgage industry is just very slow to change. The following quote from a former VP at Guaranteed Rate highlights this dynamic:

“We've been waiting for 15 years for them to allow electronic signatures on mortgage closing documents. That technology has been around forever and nobody allows it in. If they're not going to allow something as simple and verifiable as an electronic signature, what makes you think they're going to allow something as potentially life-changing or industry-changing as a VantageScore to have any role in the risk management of these assets?”

The majority of financial institutions that utilize the FICO score are relatively sophisticated and use the FICO Score in conjunction with their own risk models. Introducing an alternative credit scoring model, such as VantageScore, or modifying the current FICO scoring model would require lenders to undertake a comprehensive recalibration of their internal risk models and protracted trial period. FICO management have noted that it is close to impossible to accurately and reliably map a Classic FICO Score to a VantageScore 4.0, given that the relationship is nonlinear and changes based on the economic environment. The fact that VantageScore has not been stress-tested in a real-life economic downturn is a fairly steep impediment to lender adoption.

Financial institutions are typically reluctant to change scoring methods, and we can best see this reflected in the slow uptake of the new generations of FICO Score.

Some lenders upgrade quickly to new versions of the FICO Score, while others take much longer; observe below how FICO Scores 2, 4, and 5 are still being used for the mortgage lending market, despite FICO Score 10 and FICO Score 10 T having been released. If it was easy to switch scores, then the mortgage industry would have likely shifted to using newer generations of the FICO Score that incorporate trended data. The truth is it’s a heavy lift to change scores.

Source: MyFICO

It takes years to drive adoption of these updated and more predictive generations of FICO Score, hinting at an industry that is reluctant to change.

“So going from FICO 8 to FICO 9, it took four years before 50% of the market was on FICO 9. And I think you'll see the same kind of thing. It'll be four years again before FICO 10 is half the market. So it's a very slow adoption rate.” – Will Lansing (CEO), MS TMT Conference 2025

Back in October 2022, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) announced that a dual-score mandate would be implemented, whereby the GSEs would be required to use both a FICO Score and VantageScore on conforming mortgages. The FHFA then backed away from this proposed move. There is signal in the fact that in July 2025, after years of consultation and trying to get the industry ready for this shift, the FHFA announced that it was moving to lender’s choice, whereby lenders can choose to use either FICO or VantageScore (i.e., a somewhat watered down policy compared to the original dual-score mandate that was proposed).

A dual-score approach would simply double credit scoring costs and introduce immense complexity across the origination and securitization value chains. A Goldman Sachs research note highlighted that the FHFA had previously estimated that it would cost the mortgage industry $600 million or more to move to a dual-score mandate. These heavy implementation costs, and the fact that the absolute cost of a FICO Score is so low relative to mortgage closing costs, and that this cost is passed on to consumers, leads us to believe that there’s a low incentive for lenders to make the switch to VantageScore.

Inertia is a fairly safe bet when it comes to making changes that risk disrupting a high-value ecosystem that depends on an industry standard product like the FICO Score. There is $13 trillion worth of outstanding mortgages in the U.S.[3] – there is an extremely high bar for implementing changes that risk dysfunction in such a financially, socially, and politically important market. For this reason, we are of the view that any changes to the status quo of FICO as the credit score used in the U.S. mortgage market will be slow and marginal.

Are there examples of an industry standard being displaced?

If industry standards are so defensible, there’s merit in looking at historical examples of when those standards get displaced. We view there as being two primary ways in which industry participants will pivot away from a standard: 1) technological change leads to a new industry standard that is significantly more performant; and 2) a new standard is mandated by a regulatory body.

The inexorable changes stemming from technological innovation have led to numerous industry standards being unseated. Email usurped fax. The consumption of media content moved from VHS to DVD to Blu-ray, before changing form factor entirely with the advent of streaming services like Netflix. In the case of FICO, we are not at all worried about technological change displacing the FICO Score as the industry standard.

If we look at newer generations of FICO Score, there is typically only a minor incremental performance uplift compared to the prior generation of FICO Score. In other words, the predictiveness of scores has already begun to asymptote, and we don’t foresee a new credit scoring method materializing that can predict loan defaults at a significantly higher rate of accuracy than the FICO Score. Any improvements are likely to be incremental and minor. This militates against a step change improvement that is capable of catalyzing a broader industry shift towards a new standard of assessing creditworthiness.

We would also note that standards are most easily adopted when they are free. The unique history of FICO, whereby it kept its Scores prices both fixed and at a very low level for almost three decades, created the perfect conditions for adoption of the FICO Score as the industry standard. We deem it highly unlikely that a competitor score such as VantageScore will give away its score for free for years in order to drive adoption, particularly when we consider the unique financial incentives of the VantageScore JV (which we dissect later in the report).

Finally, as it relates to the potential for regulatory change to cause a displacement of the FICO Score as the industry standard, we believe that the disruption to the all-important mortgage industry would be far too great to make these changes.

Business History

The history of FICO is fascinating, and one that is entwined with the history of lending in the U.S. It is certainly worth exploring the company’s past in some detail to understand the significance of FICO’s contribution to improving underwriting standards and expanding access to credit in the U.S. Only then can we truly appreciate the impact that the FICO Score has had on the U.S. lending landscape and the value the FICO Score provides.

The company was founded in 1956 by engineer Bill Fair and mathematician Earl Isaac. The two had met at the Stanford Research Institute while they were working as operations researchers for the U.S. military. Fair and Isaac saw an opportunity to apply their operations research methods to the private sector in a for profit enterprise. They both put in $400 as an initial investment and set out to start a consulting business that aimed to use data to improve business decisions. The duo eventually settled on consumer lending as the domain in which they would apply their analytical efforts.

Fair and Isaac sent letters out to the 50 major U.S. lenders, requesting a meeting to explain their approach of employing statistical techniques to measure credit risk. They received one reply. A lender called American Investment Company (AIC), the nation’s fourth largest consumer finance company at the time, agreed to let Fair and Isaac analyze the company’s credit files. The resultant credit scoring system, after analyzing 13,000 “good” accounts (those devoid of significant delinquencies) and 1,000 “bad” borrower profiles, purportedly enabled AIC to reduce its bad debt charge-offs by 25% with only a 3% reduction in total loan volumes[4]. The data used was rather rudimentary: how long borrowers had lived at their current residence, whether they had a telephone, and other questions such as age and marital status. Regardless, AIC served as a proof point of the systematization of credit risk analysis which led to other lenders taking interest.

During this initial phase of the Fair Isaac Corporation, the company was a consultancy that worked on bespoke credit analysis projects for lenders, a far cry from the intellectual property licensing business FICO is today. What is so remarkable about the FICO story is that the company managed to bring statistical rigor to consumer credit analysis before the digitization of credit data.

A dissertation on the history of the Fair Isaac scorecard by Martha Ann Poon made the following comments regarding the laborious process by which the company originally generated its credit scorecards[5]:

“In the late 1950s the ability to calculate involved executing a series of physically demanding activities. Credit scoring required a steady traffic of materials back and forth, between Fair Isaac, a second party firm with access to computers and engineering skill, and storage rooms of credit operations spread out across the country. To change credit screening practices on the ground, the company had to command an intricate process of moving people, paper and things around.”

In the late 1950s and 1960s, Fair Isaac Corporation pioneered a new industry by doing the incredibly labor-intensive, manual process to generate credit scorecards. FICO was essentially turning stacks of paper (i.e., consumer credit data), using physical labor, into an easy-to-use cardboard printed table that mapped out the odds of defaulting (although the credit scoring process became increasingly automated in the ensuing decades due to improvements in computing technology). Each borrower attribute (e.g., age, time on job, delinquencies, etc.) was assigned a point value which was then tallied. This numeric score correlated with the odds of repayment, and each bank or finance company could raise or lower its own cutoff score to reflect their risk appetite and willingness to grant credit. The beauty of this new system, devised by Fair Isaac Corporation, was that it provided a standardized approach to making credit decisions that was consistent and scalable, much unlike the subjective judgment of loan officers that often fell victim to biases (cough… prejudices).

If we trace the history of lending in the U.S., much of it was done based on a character assessment and personal relationships. Obviously, it’s difficult to scale this approach, and the proliferation of consumer credit with the advent of the credit card demanded a more rigorous, consistent, and fair approach. FICO’s credit scorecards came at the right time and place, particularly when we consider some of the later regulatory changes to fair lending practices.

The 1970s were a period of immense social change in the U.S., and this was reflected in a number of hearings conducted by Congress during that era to create equal credit opportunity as a civil right[6]. Legislation was subsequently introduced that banned creditors from basing lending decisions on factors such as race, religion, sex, marital status, or age, promoting the idea that credit should be granted based on merit rather than an individual belonging to some group which is beyond their control. While the intent of this regulation was noble, it posed difficulties for lenders. The Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) which was passed in 1974 required lenders to provide reasons for why a borrower was turned down for a loan. Over time, the objectivity of a credit scoring method such as that offered by FICO provided the necessary cover for lenders to point to their compliance with the definition of fairness as espoused by the ECOA. As is often the case with regulation spurring change, these new fair lending rules accelerated lender adoption of the credit scoring systems that FICO offered.

Back in the 1800s, the bulk of credit activity in the U.S. was between lenders and commercial enterprises (early forms of credit scoring can be traced back to the 1830s when local credit bureaus helped firms decide whether to extend trade credit[7]). The corollary of this is that most Americans paid cash for goods; borrowing was deemed risky and irresponsible. It wasn’t until the 1900s that the advent of the motor vehicle, which was a higher sticker price item relative to average wages, necessitated some inventive forms of financing to drive sales. General Motors created the General Motors Acceptance Corporation (GMAC), making car ownership possible by popularizing the concept of the installment plan (as a fun fact, GMAC was the precursor to Ally Financial).

Retailers similarly adopted these installment plans. However, in the early 1960s, retailers began transitioning from installment plans to revolving credit plans, where customers paid a percentage of the balance and interest accrued on the rest (and notably there was no risk of repossession upon default, as there was in an installment plan arrangement). This shift was what paved the way for the modern credit card.

It wasn’t until the late 1960s that we saw unsecured consumer credit from financial institutions become a more meaningful part of the lending landscape. Up until that point, most of the credit granted to consumers was extended by retailers. This rapid expansion in consumer credit prompted a desperate need for the systematization of credit evaluation at scale. While FICO was making inroads on this front, the data used in its scorecards was siloed within the banks and retailers that it was commissioned by to provide bespoke scoring systems. What was needed was a scaled, centralized repository of consumer credit data.

Over the course of the twentieth century, there was significant consolidation of the U.S. credit bureaus – the companies that controlled the consumer credit data. This industry consolidation accelerated following the introduction of the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) in 1970, which introduced a regulatory framework that favored the larger credit bureaus that could afford to make the necessary investments in infrastructure to be compliant (many of the smaller bureaus lacked the capital and technical resources to make these upgrades).

This culminated in the emergence of the big three credit bureaus: Equifax, TransUnion, and Experian. These three credit bureaus provided exactly what FICO needed in terms of centralized credit data at scale – a development that was made possible by the digitization of data that stemmed from computing advancements. It was thus in 1984 that FICO released what was called PreScore. FICO’s PreScore used credit bureau files to screen consumers for pre-approved credit card offers (rather than blanketing an entire region with solicitations for credit, only to reject a large portion of those unscreened applicants[8]).

While the PreScore was a standardized score used for marketing credit products, it wasn’t until 1989 that FICO introduced the FICO Score, which was used as a general-purpose credit score to standardize and automate the assessment of credit risk. Rather than the hitherto manual review of consumer credit applications – which were time-intensive, costly, subject to the biases of the loan officer, and often saw inconsistent outcomes – the FICO Score underpinned an automated credit underwriting process that was fairer, more consistent, and expanded access to credit. The FICO Score also emerged at an opportune time – the recession in the late 1980s led to an increasing number of credit card delinquencies. Of the more than 200 million Visa, MasterCard and Discover card products at the time, 14% were subject to credit scoring in 1989, which jumped to more than 50% in the early years of the 1990s[9].

The pivotal moment for the FICO Score came in 1995 when the GSEs Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac directed lenders to use FICO scores for all new residential mortgage applications. Notably, this was when Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were for-profit enterprises owned by private shareholders; these corporations voluntarily adopted the FICO Score, given that lenders were already using it to evaluate credit risk in mortgage and non-mortgage markets (i.e., FICO’s monopoly in U.S. mortgages was not granted by government decree but rather guided by market forces). This cemented the FICO Score as the industry standard for U.S. residential mortgages, but lender adoption more broadly also saw the FICO Score become dominant in other verticals such as auto loans and credit cards.

The erroneous notion that FICO is only dominant because of its government mandated use in the conforming mortgage loan market is best rebutted when we see that the majority of FICO Scores are used outside of mortgage originations. In a blog post by the President of FICO’s Scores business, Jim Wehmann revealed that 99% of FICO Scores are used outside of mortgage originations.

“In fact, the vast majority, approximately 99%, of FICO Scores used for decisioning across the consumer credit industry are used outside mortgage originations. Total mortgage originations, including GSE-purchased mortgages, constitutes only 1% of all FICO Scores used for decisioning across the consumer credit industry.”

This recount of FICO’s history helps us better understand the importance of FICO in the U.S. consumer credit ecosystem. But to properly appreciate FICO as an investment, and to assess the company’s future growth prospects, we must understand the company’s special price increases.

The remainder of this 16,000+ word deep dive is reserved for paid subscribers. We cover FICO’s special price increases, the royalties FICO receives in a typical mortgage loan origination, the economics and incentives of the CRAs (including why the CRAs are incentivized for FICO to continue raising prices), as well as views on where FICO’s scores pricing might go in future years. Consider becoming a paid subscriber to receive full access to the remainder of this FICO report.