The Trade Desk (TTD) - A Champion of the Open Web

Bristlemoon's exploration of the murky, complex world of ad tech

Welcome to the fifth Bristlemoon Capital stock write-up. It has been five months since publishing our first post, and this report on TTD will mark more than 80,000 words of content being published cumulatively over that period. We recently made the decision to monetize this publication, and we are immensely grateful for the many subscribers who have already converted to paid subscriptions.

Please see the following links for our previous reports on EYE, RH, Copart, Match Group, as well as our appearance on the Business Breakdowns podcast discussing Match.

Bristlemoon readers can also access some of the resources we used to research TTD via the links below:

Tegus – Bristlemoon readers can enjoy a free trial of the Tegus expert call library via this link

Koyfin – Bristlemoon readers can get 20% off a Koyfin subscription via this link

Table of Contents

Introduction & company history

Programmatic advertising and the ad tech supply chain

Programmatic buying models

Ad tech supply chain

Walled gardens vs the open web

Business overview

A champion of the open web

Financial performance

Platform & technology

Competitive differentiation

Scale

Independence

Close relationship with ad agencies

Transparency & control

For paid subscribers:

Growth drivers and other opportunities

Connected TV

Overview

Market fragmentation

The shift to programmatic

Programmatic fees

Programmatic CPMs

Will CTV be 100% biddable?

TTD’s market share

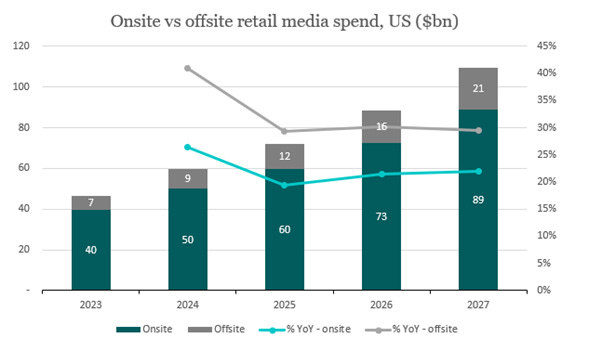

Retail Media

Overview

Onsite vs offsite

In-housing of retail media

TTD’s offsite retail media partnerships

How big is the opportunity?

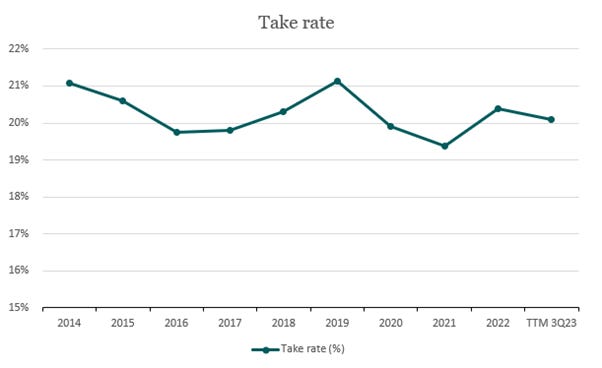

Take rate sustainability

Overview

Impact of CTV mix

3rd party cookie deprecation

OpenPath and Supply Path Optimization

Unified ID 2.0 and the deprecation of cookies

UID2

Privacy issues

Signal loss

Impact of cookie deprecation

Valuation considerations

Key Takeaways

The Trade Desk is the largest independent Demand Side Platform in the programmatic advertising industry, used by advertisers to automate the process of buying ads on the open web. Led by enigmatic and promotional co-founder Jeff Green, the company has delivered phenomenal growth and a mind-blowing 40x share price return in just over seven years as a public company.

The programmatic ad tech supply chain is highly opaque and rife with conflicts of interest and fee gouging. The Trade Desk built its reputation on independence, transparency, and exclusively serving the interests of its ad buying clients. A prescient decision to align with the advertising agency holding companies early on allowed The Trade Desk to turbocharge its growth in an industry where scale begets scale. As the largest independent DSP, the company is poised to be the key beneficiary of industry consolidation.

The Trade Desk is overweight two of the fastest growing channels in digital advertising: connected TV and retail media. CTV is rapidly taking share from linear TV in both share of time spent and share of ad spend, and management spin an appealing narrative around the company’s opportunity in CTV advertising. We challenge management’s claims of perfect market fragmentation, an inevitable shift to fully programmatic ad sales, and higher industry CPMs. Instead, we find a market that will be dominated by a handful of powerful players capable of erecting walled gardens, a structural supply-demand imbalance favoring ad sellers over ad buyers, and industry economics that will be less favorable going forward.

Retail media is a long-term opportunity and one that we believe is even more challenging for The Trade Desk to exploit given its lack of required supply-side capabilities, a lack of 1st party data, retailer pushback to ad tech fees, and a changing privacy/cookies landscape that risks degrading the efficacy of offsite retail media advertising.

We believe the company’s unerringly stable take rate of ~20% since IPO may come under increasing pressure in the coming years with headwinds from an evolving CTV mix and Google’s planned deprecation of 3rd party cookies in the Chrome browser, which will impact (very) high fee data sales. Management is attempting to mitigate fee pressure through supply path optimization, a.k.a. bypassing other intermediaries in the supply chain to retain more fees for itself, which every other prominent ad tech intermediary is also doing. The company is also trying to offset the loss of signal from cookie deprecation by implementing its proprietary Unified ID 2.0 identifier solution, though we are not confident such alternative deterministic IDs are scalable or will pass regulatory scrutiny in the long run.

Ultimately, we find The Trade Desk to be a fantastic product, a sound business with good prospects if ignoring the hype, but an unattractive stock that is priced to perfection with no margin of safety for the myriad of risks that shareholders face.

Introduction

If a movie were to be made about digital advertising, Google would be the Roman Republic and Jeff Green would be Spartacus. Green, the enigmatic co-founder of The Trade Desk, would lead his band of rebels in a fight for the freedom of the Open Internet against the tyranny and oppression of the Google ad empire. Through a combination of prescient early decisions, a healthy dose of right-time-right-place, and an unwavering commitment to serve the interests of its core clients in an industry that is rife with conflicts of interest, The Trade Desk has achieved something truly remarkable: a 40-bagger in seven years as a public company.

This deep dive marks our first foray into the murky world of advertising technology (ad tech). We found the industry to be opaque, unnecessarily complicated, and challenging for non-practitioners to fully understand all the nuances. As the poster child of independent ad tech and a current market darling, The Trade Desk seemed like the logical place to start. We caution readers again that this report presents our initial research into ad tech and The Trade Desk; we are not authorities on either and shouldn't be considered as such. We invite readers to partake on a journey with us as we learn about both industry and company. As always, any pushbacks or qualifications to our views and conclusions are greatly appreciated.

The story so far

Jeff Green’s entrepreneurial beginnings

The story of The Trade Desk is inextricably linked to the story of the company’s co-founder, Jeff Green. Green, a Utah native, earned a Bachelor of Arts degree from Brigham Young University in 2001 and then later a degree in marketing communications from the University of Southern California[1]. It was during his studies that Green gained experience as a digital media buyer at an agency during the 2000 dot-com crash[2]. Green later recounted how these formative experiences fueled his passion for digital advertising:

“I fell in love with digital advertising then and there. I loved the fusion of left brain and right brain. I got be to be creative and imagine a new hypothesis to make advertising better and then we’d get to look at the data and validate or disprove the idea. Back then I realized the advantages of data-driven digital advertising, which allowed advertisers and marketers to target and also measure ads like never before. I’ve basically spent most of the last 20 years trying to make that more pervasive.”[3]

Following his tertiary studies, Green started his professional career as a technical account manager within the MSN division of Microsoft, based in Salt Lake City. It wasn’t too long after this that Green started his own business. In 2003, Green founded a company called AdECN, one of the world’s first online ad exchanges. AdECN was akin to a stock market for digital ads (note that Jeff Green got his securities broker license in his twenties and had previously worked in the investment division of an insurance company).[4]

In 2007, four years into his journey running AdECN, Jeff Green’s career had come full circle, with Microsoft agreeing to acquire his company for an undisclosed sum. AdExchanger speculated on the purchase price, writing about the company being acquired “for what some suggest is in the $50-75 million range”[5]. Green continued to run AdECN within Microsoft, and he took on additional responsibilities including overseeing the reseller and channel partner business which included monetization of Facebook ads, Fox Sports, MSNBC, Hotmail and several other internet sites[6].

The Trade Desk – the Goldman Sachs of online advertising

It was during this second stint at Microsoft that Jeff Green met David Pickles, his soon-to-be co-founder and CTO. In 2009, Jeff Green and David Pickles co-founded The Trade Desk. Within the confines of Microsoft, Green was hamstrung in his ability to enact his ideas for the future of digital advertising technology. By starting his own company (again), Green reclaimed agency to continue building without “the bureaucracy and internal politics”[7] that came with being nestled in a bigger firm.

In a February 2023 Invest Like the Best podcast interview, Jeff Green explained his motivations for starting The Trade Desk:

“In my previous company, I was very frustrated by the fact that online advertising was transacted the same way traditional advertising was, which was over martini lunches. If you watch Mad Men, that's how it was at the beginning of the Internet, too, more casual clothes, but same process. It just frustrated me why couldn't the advertising ecosystem look more like the equities markets. Why couldn't we have a centralized exchange? In my 20s, I was young enough, naive enough, dumb enough, ambitious enough to try to create that and change all of it. And I happen to be lucky enough to be one of the people that perpetuated that movement and created that. So there were a number of us, I wasn't the only one. But there were a number of us that created ad exchanges that now have changed advertising. So those are at the center of the ecosystem.”

In Green’s previous role at AdECN, he noted a lack of sophistication in the ad buyers. Despite the creation of ad exchanges, ad buyers still defaulted to paying $0.50 for every impression. They would bid the same price for every impression in a world where every impression was clearly not created equal. Green’s frustration with the underutilization of ad tech’s capabilities prompted him to start The Trade Desk and exclusively represent ad buyers to maximize the value of their ad dollars within the digital ecosystem.

Green once told socalTech that “[w]hat we’re building now is a system much more like the Goldman Sachs of online advertising”. The platform would offer a marketplace enabling buyers to place specific ads in-front of a precisely targeted audience[8], utilizing data to automate these decisions in real-time.

Taking The Trade Desk public

The Trade Desk raised $2.5 million from Founder Collective and IA Ventures in a seed round in March 2010[9]. In addition to the two lead investors, there were a number of strategic investors who contributed capital in a second and final tranche for the seed round. These investors included Jerry Neumann, who previously ran the interactive media arm of Omnicom, and Josh Stylman, who was co-CEO and Managing Partner of Reprise Media, a division of Interpublic[10].

In a 2021 article covering the launch of the company’s internal venture capital arm, TD7, it was disclosed that the “TD7” name derived from the $7 million in venture capital it took for The Trade Desk to become profitable[11], implying an additional $4.5 million of venture capital from the strategic investors. Co-founders Green and Pickles asked for an amount of money needed to get the business to profitability, and The Trade Desk was able to achieve profitability in 2010, the company’s second year of operation.

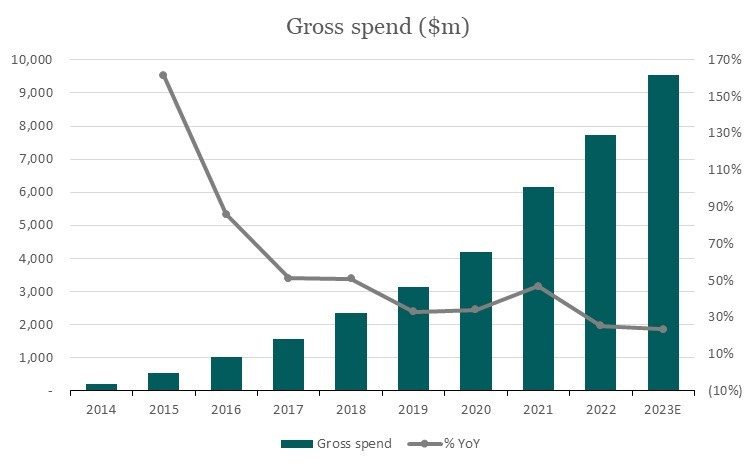

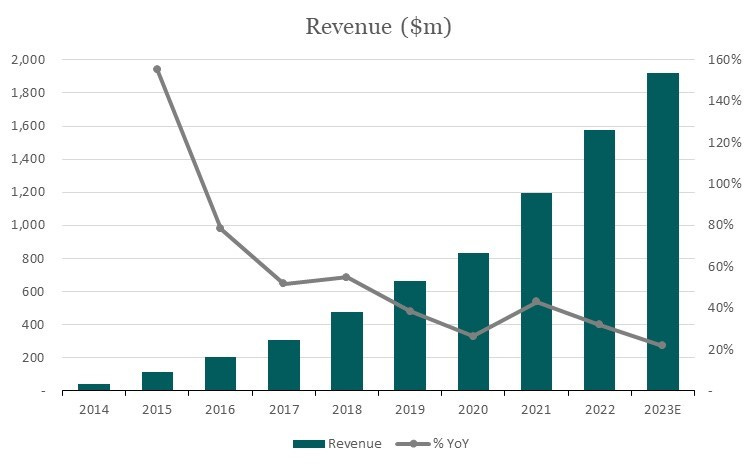

The Trade Desk completed its IPO on September 21, 2016, trading on the Nasdaq under the ticker TTD. The company went public at $18.00 per share and finished its first trading day at a price of $30.10 per share, a 67% increase. From TTD’s S-1 filed in 2016, the company produced $113.8 million of revenue in 2015, a 156% increase over the $44.5 million of revenue produced in 2014. Growth in TTD’s adjusted EBITDA was even more explosive. The company generated $39.2 million of adjusted EBITDA in 2015, growth of 589% over the $5.7 million of adjusted EBITDA produced in 2014. The company was notching up astonishing growth rates and investors were scrambling to own this business.

The company’s share price performance since the IPO puts TTD in the compounder hall-of-fame. If we adjust the IPO price for the ten-for-one split of the company’s common stock that occurred on June 17, 2021, we can calculate a $1.80 split-adjusted IPO share price. Given the share price is currently around $74, this equates to a 41x increase in value since the September 2016 IPO. This works out as a 64% CAGR over seven years. If we were to adjust for the day-one share price pop, and instead use the $3.01 split-adjusted price in our calculation, this still produces a 53% CAGR.

Source: Koyfin (Bristlemoon readers can get 20% off a Koyfin subscription via this link)

Before we can get into what makes The Trade Desk special and what the future potentially holds, we must first establish a foundational understanding of the programmatic ad tech supply chain in which the company operates. Readers familiar with the ad tech ecosystem can feel free to skip the following section.

Programmatic advertising and the ad tech supply chain

Programmatic advertising refers to the use of technology and algorithms to automate the process of buying digital ad impressions. It offers improvements over more traditional manual buying methods in terms of cost savings, time savings and better targetability of ads. The term “programmatic” refers to not one but a range of buying models with varying levels of automation, targeting, data activation and control retained by the advertiser and publisher. The price at which ads are bought and sold at is typically referred to as CPM (cost per mille or 1,000 impressions) or some other cost-per-unit that can typically be converted back to an effective CPM.

Programmatic buying models

Source: Bristlemoon Capital

Programmatic Guaranteed

The most basic yet highest priority form of programmatic buying is Programmatic Guaranteed (PG), which are essentially digitalized versions of direct deals. PG deals are typically negotiated as one-on-one deals between an advertiser and publisher, have a fixed price and a guaranteed volume of impressions. The only automated decision is whether or not to buy each ad impression as they arise, noting that the advertiser must buy (and the publisher must serve) the agreed-upon volume of impressions for the campaign; everything else is negotiated beforehand.

The benefit to the advertiser is that it receives a guaranteed volume of premium inventory (i.e., the most engaged audiences) for a campaign at a fixed price but surrenders a lot of flexibility in terms of using data to target specific audiences. The benefit to the publisher is that it retains the greatest control over the ads served on its properties and achieves a favorable fixed price, but risks underpricing its inventory relative to an open auction with price discovery. Because the advertiser and publisher deal directly, the risk of ad fraud is greatly reduced. PG is typically only used by “premium” publishers with the most sought-after inventory that can fetch a high negotiated price.

Preferred deals

Next in the order of priority are preferred deals, which are identical to PG except the impressions are not guaranteed. Instead, the buyer gets a “first look” at premium ad impressions and can choose to buy or pass at the negotiated price. Because there is no obligation to buy, there is more scope for the advertiser to activate audience data to inform the buying decision even though the pricing remains fixed. Impressions that are not bought are passed down the priority ranking to private or open auctions.

Private Marketplace

The first of the auction models is the Private Marketplace (PMP), which as the name implies is available by invitation only. A publisher of premium inventory invites a group of advertisers into a PMP, and the advertisers use real-time bidding tools to participate in a private auction. The invite-only nature of a PMP makes it safer for both publishers and advertisers. Publishers invite only trusted brands and demand partners into the auction and thus retain some element of control over what ads are shown where, and advertisers know their ads will be shown in brand-safe environments with minimal ad fraud. CPMs may also be higher as: 1) there is a real-time auction albeit with a select group of bidders; and 2) the publisher, advertisers and their ad tech partners can share and leverage 1st and 3rd party data in a safe environment to allow better audience targeting, which can drive higher CPMs and higher return on ad spend (ROAS).

For the above three buying models – PG, preferred deals and PMP – the buyers and sellers are known to each other and can negotiate the terms of their exchange and build advertiser-publisher relationships over time. This has implications for ad tech partners as we will discuss later in the report.

Open auction

Finally, there is the open auction or open exchange, which is where real-time bidding occurs in an open marketplace of publishers and advertisers. Publishers will specify certain parameters around their inventory (e.g., format, ad type), set floor prices and send their bid requests out to the open market for any eligible advertiser to bid on. Advertisers can set up automated campaigns that will automatically bid on any bid requests that match the advertiser’s criteria.

The publisher does not know who the winning bidders are and what kind of ads will appear on their properties. They also face an elevated risk of data leakage as each bid request sent carries a snippet of valuable 1st party publisher data that can be scraped by malicious actors. Advertisers do not always know what kind of inventory their automated campaigns are bidding on or what content their ads will appear next to. They are also subject to a heightened risk of ad fraud such as bidding on zombie audiences or Made-for-Advertising (MFA) inventory with zero value.

Open auction CPMs can be mixed as there is an unknown quantum and quality of bidders, though open exchanges generally have a much larger supply of potentially lower quality impressions compared to the other programmatic channels discussed above. It is for these reasons that premium publishers with premium inventory typically reserve open auctions for any remnant inventory not sold through other means.

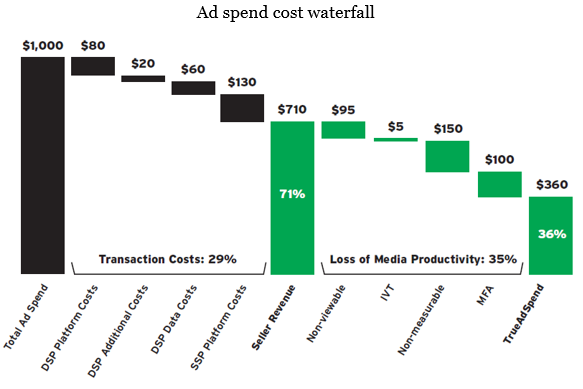

The ad tech supply chain

In order to facilitate the automated buying and selling of ads, an ad tech ecosystem has developed over the past three decades to serve digital advertisers and publishers. To say that the ad tech supply chain is needlessly complicated is a gross understatement. An ad dollar leaving an advertiser’s bank account will typically pass through 4-5 intermediaries before reaching the publisher’s pocket depending on the programmatic buying model, not including the numerous vendors to those intermediaries who also take their cut of fees. By the time the original ad dollar reaches the publisher, it has typically shrunk to less than seventy cents.

Below we provide a brief introduction to the key participants of the ad tech supply chain.

Source: Redburn. Note: DSP = demand-side platform; SSP = supply-side platform

Advertiser – the party with the ad budget looking to buy ad impressions to promote their product, service, or brand.

Agency – an organization that manages the ad buying process on behalf of advertisers. Agencies typically provide the hands-on-keyboards workforce to run ad campaigns for their clients. They can exert significant influence on how their clients allocate or spend their ad budgets. “Ad buyer” can refer to the agency or the advertiser if buying direct. Agencies are either independent or subsidiaries of the large agency holding companies (“holdcos”) – WPP, Omnicom, Publicis, IPG, Dentsu and Havas.

Publisher – owner or operator of media properties with advertising inventory (i.e., ad space) that can be sold to ad buyers. Can range from “traditional” media operators such as newspapers, cable networks and connected TV platforms through to special interest websites, e-commerce marketplaces and Facebook.

Demand Side Platform (DSP) – ad tech vendor to advertisers and agencies, providing the automated ad buying tools to bid on auctions, run and optimize ad campaigns, and connect into supply partners be they publisher direct, an ad exchange or an SSP. TTD is a pureplay DSP.

Supply Side Platform (SSP) – ad tech vendor to publishers, providing the technology for publishers to manage and automatically sell their ad inventory. An SSP manages the bidstream – the stream of bid requests that emerge as viewers navigate around a publisher’s property – and finds optimal placements for ads to maximize the publisher’s yield. An SSP integrates with demand partners such as ad exchanges or DSPs to bring advertisers to the publisher’s audience.

Ad exchange – a marketplace where ad buyers, DSPs, SSPs and ad sellers connect to transact through automated auctions. Auctions are typically conducted on an ad exchange but can also be run directly by an SSP if it has the capabilities – for example in a private marketplace auction. Many SSPs also own an ad exchange and ad server, with Google Ad Manager (SSP), Google AdX, and Google Ad Server being the most prominent example.

Ad server – ad servers sit at both ends of the supply chain. Advertiser ad servers store ad creatives (the images, audio and video that comprise an ad) and provide some measurement capabilities. Publisher ad servers have a more prominent role in ad tech as they determine the winner of an auction, which ads are placed where, and handle some ad targeting and measurement functions.

Other vendors in the ad tech ecosystem outside the remit of this TTD deep dive include (but not limited to):

Data management platforms which collect or scrape 3rd party data to be sold to advertisers via DSP integrations;

Measurement and verification partners that measure campaign performance metrics such as reach, brand lift, conversions etc, and independently verify ads for viewability, brand safety, ad fraud etc.; and

Data clean rooms and customer data platforms which manage sensitive 1st party data and personally identifiable information in a safe environment, allowing this valuable data to be used to build and target audiences.

Below is a sample of leading ad tech ecosystem participants:

Source: Morgan Stanley

Walled gardens and the open web

The digital advertising landscape can be separated into two continents – the walled gardens and the open web. The walled gardens, as the name suggests, are platforms or media properties that are largely closed off to external participants in the ad tech supply chain. The media owner typically controls the demand side tools that advertisers require to bid for ad impressions on its owned & operated (O&O) properties, the supply side tools for managing inventory, bid requests and auctions on its properties, and the ad server that serves the winning ads to the properties’ audience. The most prominent walled gardens (ex-China) are Google and Meta, and tier 2 walled gardens include Amazon, TikTok, Snap and X (Twitter) among others.

The key criteria for walled gardens are 1) having massive, internet-scale audiences that can attract ad buyers directly, and 2) having highly valuable 1st party data that is only available within the walled garden. The open web, on the other hand, represents the millions of other publishers on the Internet vying for a share of digital ad dollars. These publishers range from household names such as Disney, Walmart and The New York Times, through to the long tail of unheard-of websites with minimal traffic.

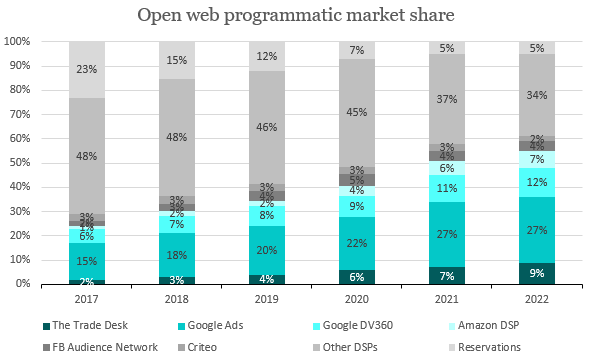

Jounce Media[12] forecasts open web programmatic advertising to reach ~$88 billion in 2023, a CAGR of 5% since 2017, compared to over 30% CAGR for the walled gardens. Google is so dominant in the ad tech industry that it serves ~40% of all ad dollars transacted on the open web, with the remainder mainly being served by the independent ad tech supply chain. TTD is the largest independent ad tech provider with $7.7 billion in gross advertising dollars flowing through its buying platform in 2022. TTD has just under 10% share of the market.

Source: ANA, Jounce Media. Walled Gardens includes Meta (Facebook & Instagram), YouTube, Amazon properties, and “Challenger” gardens TikTok, Twitter, Snap, LinkedIn, Pinterest etc.

Source: Jounce Media; Bristlemoon Capital

A champion of the open web

The Trade Desk provides a self-service, cloud-based programmatic ad-buying platform. TTD’s clients are ad buyers. These ad buyers use TTD’s platform to plan, manage, optimize and measure their digital advertising campaigns. The platform allows clients to execute ad campaigns across various advertising channels including video and connected TV, display, audio, digital out of home, and social. It also allows ad campaigns to span across a range of devices including computers, smartphones, smart TVs and streaming devices. As a pure-play DSP, TTD doesn’t own or operate any of its own ad inventory. Instead, it obtains a supply of omnichannel inventory from over 100 directly integrated ad exchanges and SSPs.

TTD has positioned itself as the go-to independent open web ad buying platform for large, sophisticated advertisers typically represented by ad agencies. As of December 2022, the company has over 1,000 clients, consisting primarily of advertising agencies under the large agency holdcos and tier 2 independent agencies, with each agency likely representing a multitude of advertisers.

Clients are defined as parties that have signed agreements with the company and spend more than $20,000 on the platform, though we have anecdotally seen minimum spend requirements of over $100,000 per month for prospective direct clients. Smaller advertisers and agencies are required to go through resellers. Management have stated that they are not interested in onboarding sub-scale clients and are more focused on growing share of ad spend at existing clients. TTD’s client retention rate has exceeded 95% for 2022, 2021 and 2020.

Source: Redburn; Company filings

TTD’s clients are diversified across verticals, with no vertical representing more than a high-teens percentage of total gross spend on the platform. This derisks the revenues to an extent as TTD is not overexposed to any single industry cycle, though as we saw in Q3 2023, the company is not immune to broader weakness in the digital ad market, particularly within the CTV channel.

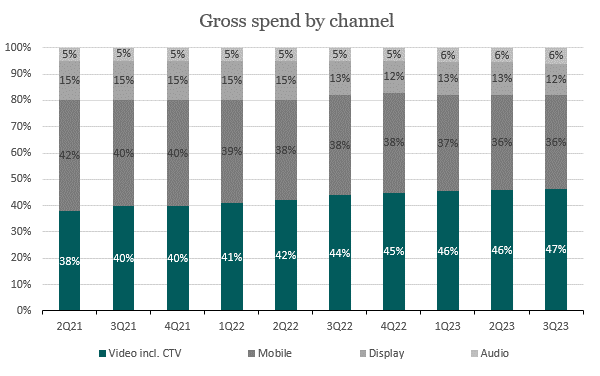

Source: Bristlemoon Capital; Company filings

Management doesn’t disclose quantitatively the gross spend by channel mix, but we know video is the largest channel and CTV is the vast majority of video. CTV is the fastest growing channel and largest opportunity for TTD, followed by retail media which is more nascent for TTD but potentially just as large an opportunity if one believes in management. We will discuss both CTV and retail media in detail later in the report given their importance to the TTD thesis. The mobile web and display channels are the more legacy channels for TTD and should continue to decline in importance over time. Redburn estimates the display channel may have even declined slightly into 2023 based on qualitative comments around channel mix, with growth largely driven by CTV and to a lesser extent retail media. Finally, audio and digital out of home are fast-growing emergent channels but relatively small for TTD and unlikely to move the needle for shareholders.

Source: Redburn estimates; Bristlemoon Capital estimates (based on qualitative comments)

Financial performance

TTD’s unique technology and strong competitive differentiation has enabled it to deliver outstanding financial performance. Since the company’s IPO in 2016, it has compounded gross spend and revenue at a 38% CAGR, handily outgrowing the broader open programmatic market and taking 700 bps of market share between 2017 and 2022. TTD collects a percentage of the client’s media budget as a fee for using its platform. Said another way, TTD has a take rate revenue model. The percentage take rate has remained stable at ~20% of gross spend since IPO. We only mention this briefly here so readers have an idea of TTD’s revenue model, as we have a lot more to say about the take rate later in the report.

Source: Bristlemoon Capital; Company filings

The company has also delivered 800 bps of adjusted EBITDA margin expansion, though the picture is one of deleverage once we factor in share-based compensation.

Source: Bristlemoon Capital; Company filings

We would note here that this report is less quantitative than our previous reports simply because TTD is a very high growth business. We believe qualitatively analyzing the key growth drivers and risks for an industry that is evolving rapidly is more informative for the reader than agonizing over NPVs or earnings power that are highly sensitive to growth rates.

Platform & technology

From our research and conversations with industry experts, we heard mixed opinions regarding the TTD platform capabilities and user experience, with some saying the platform had a steep learning curve and required a lot of training from TTD instructors, and others saying the platform was straightforward to use and the capabilities were somewhat underwhelming for experienced, sophisticated traders. On balance, the views leaned more positive in terms of both capabilities and UI/UX.

One thing that does separate TTD from other DSPs and is perhaps not well highlighted by management or understood by investors, is the platform’s unique bid factoring architecture. Bid factoring is TTD’s original technical claim to fame and allows traders to apply a factor or weight to elements of the bidstream such as ad size, site, device etc. that are more likely to produce the best ad performance. The platform takes these factors and computes the value of impressions in real time and adjusts the CPM bid accordingly.

To understand how this differs to competitors, we need to understand how programmatic ad campaigns are actually constructed. The basic “instruction” for an automated ad buying tool is the line item, which consists of multiple elements such as a budget, a CPM bid, an ad creative, and the targeting criteria. When a request in the bidstream meets the criteria of a line item, a bid is submitted at the preset CPM. Campaigns are essentially a collection of line items. In order to adjust or optimize an ad campaign in flight, line items need to be edited or new items inserted, which can result in campaigns growing to hundreds, thousands or even hundreds of thousands of line items. For an agency trader stretched thin across dozens of campaigns for different clients, managing these thousands of line items can be a nightmare.

TTD’s bid factoring architecture simplifies this by applying factors to elements of a campaign across multiple line items – e.g., adjusting all line items targeting the California region with iOS as the device type up by X% regardless of other targeting criteria. According to one recent Tegus interview with a company former, other DSPs cannot replicate the flexibility of TTD’s bid factoring because they (the competitors, including Google DV360) are built on a legacy line item-based architecture.

“The old DSPs, what they're doing now, they do something called ad grouping, which is similar, but not the same in that, they can let you group [line items] together and it's still very manual for the trader…it's so rigid that you could basically say, because of this ad group or this grouping have similar [performance] traits, I'm only going to bid this much on this group…That's what the old DSPs are copying, but it's different than what The Trade Desk is doing because The Trade Desk can not only just change prices, they can change the geo, they can change the demo target, they can add data into one part of it, they can do different things with those groupings that these other companies can't do.”

But we believe bid factoring may be less of a differentiator now that other DSPs have expanded their custom bidding capabilities. For example, Google DV360’s custom bidding algorithms appear to be more powerful and robust than bid factoring, although they require greater user sophistication to properly utilize the additional functionality. DV360 also offers bid multipliers which is similar to bid factoring as far as we can tell but can’t be used in conjunction with automated bidding algorithms. With TTD’s bid factoring, traders can layer manual bid factors on top of the automated bid optimization tool. We reiterate that not being programmatic ad buyers or ad tech operators, we find it objectively difficult to assess the technical capabilities of one platform against another.

Just to highlight the differing opinions on TTD’s tech once again, another interesting perspective we heard was that historically, TTD was not really a technology company in terms of building ad tech infrastructure and lacks the technical engineering capabilities to do so. Within the ad tech stack, there is ad tech infrastructure that sits at the base, and ad tech applications or platforms that sit on top (such as TTD’s ad-buying platform).

A crude analogy to the financial markets would be the “plumbing” that enables trade execution, clearing and settlement to occur, and the trading “platforms” like Robinhood that sit on top. We are not sure what to make of this view as it could not be corroborated, but it may become pertinent to a “build vs buy” question as TTD seeks to expand further into retail media and internationally where the ad tech ecosystem may not be as developed.

In any case, we do not believe technology moats are a source of durable competitive advantage in tech-forward internet-scale industries such as digital advertising. The topic of moats is a discussion for another day, though this article by Jerry Chen of Greylock Partners is a good explainer as to why technology in and of itself has become a shallower moat. Therefore, we advise investors to not overweight the technical claims made by management teams, especially if they cannot verify first-hand any exuberant assertions that are made. Given TTD’s track record, it is clear that the technology is good enough, and management has been active in upgrading the capabilities and UX of the platform.

The Trade Desk platform components

Here we highlight the key components of The Trade Desk platform.

Solimar is TTD’s revamped user interface that consolidated various tools in the TTD arsenal onto a single platform. The platform offers advanced goals-based media buying and optimization using TTD’s machine learning tool, Koa, advertiser 1st party data onboarding and a measurement marketplace. We have heard mixed feedback on the ease of use of TTD’s tools, with some saying they are easy enough for a fresh graduate agency trader to use and others saying the tools are catered to sophisticated buyers and can require over 12 months of training to master, but Solimar purportedly simplified the user experience and the visualization of campaign performance.

Kokai (Japanese for “open sea” or “open to the public”), announced in June 2023, is the next iteration of the TTD platform that “incorporates major advances in distributed AI, measurement, partner integrations and a revolutionary, intuitive user experience”. While this is admittedly a cryptic string of buzzwords, it appears Kokai will leverage more machine learning (ML) algorithms across the media buying workflow, especially on the measurement side where it may have been lacking previously. Note however that the new measurement features rely on unproven identity solutions in a post-cookie environment. Part of this platform update includes a new user interface inspired by the Periodic Table which has seemingly received mixed reactions. See this Reddit thread for some entertaining takes on the Kokai launch video, including this zinger from a purported TTD employee:

“Made a throwaway [account] for this. The table is JG's idea. We tried to stop it, but he wants it and it doesn't matter what we say. For the record, most of us think it's bad. It's terrible UX. Of course it's terrible; it was designed by someone who doesn't have an ounce of UX design experience. That table that was shown was literally something JG drew up over a weekend in MS paint it something. Like, it's atrocious. But JG won't meet with anyone but his yes-men who just blow rainbows up his ass, so he probably doesn't know that it's bad and that users will hate it.”

The pervasiveness of Jeff Green’s presence and influence across the company at all levels of decision making was reiterated by several company formers we heard from.

Koa is TTD’s AI tool launched in 2018 that initially provided ML campaign optimization recommendations. It has since added the ability to automatically optimize performance and spend in real time against certain KPIs and create custom audience profiles and segments to target. Koa is also a bid shading tool that aggregates and evaluates past bid data to predict the optimal bid rate for first-price auctions to help clients from overspending.

Galileo is another recently launched tool for advertisers to onboard their 1st party customer data in a privacy-safe environment for use in campaigns to target new customers. Galileo incorporates integrations with major CRM, customer data platform and other data and clean room providers. The tool uses Unified ID 2.0 (which we discuss later in the report) to match audiences across publishers, devices and channels in a purportedly privacy-safe manner.

Given the importance of data (advertiser 1st party and 3rd party data) to programmatic advertising, TTD integrates with over 200 3rd party data providers which largely helps mitigate TTD’s own lack of 1st party data due to not being a walled garden or owning/operating any media.

The Kokai user interface – UI design faux pas? Source: The Trade Desk

Competitive differentiation

Now that we are familiar with the ad tech supply chain and TTD as a business, how does the company differentiate itself from competing DSPs?

1) Scale

As the largest independent DSP in the ad tech ecosystem by some margin, TTD benefits from scale in ways that competing independent ad tech vendors simply cannot match. Beyond the obvious benefit of greater fixed cost leverage with more ad spend and revenue on the platform than competitors, TTD is well positioned to be the primary beneficiary and an accelerant of industry consolidation such that scale begets scale.

When it comes to programmatic advertising on the open web, ad demand is finite while the supply of ad inventory is effectively unlimited. This means benefits of aggregating demand are much higher than aggregating supply – that is to say, scale is a defining characteristic of DSPs. Advertisers and agencies want to consolidate their budgets under as few DSP partners as feasible for a number of reasons:

Higher spend through a single platform not only drives volume discounts but also provides more unified campaign data for evaluating the efficacy of omnichannel ad campaigns;

Allows for more effective frequency capping (the number of times a user is shown an ad) across publishers and channels;

Enables wider audience reach with ideally more unique audiences and less overlap;

Mitigates the risk of bidding against oneself if multiple DSP partners receive bid requests for the same ad impression; and

Increases the value of 1st and 3rd party data by activating available data against a higher volume of ad impressions.

For a large advertiser, it is a no-brainer to allocate a majority of the ad budget to a few of the largest DSPs (e.g. Google DV360, TTD and Amazon DSP) and partner with smaller specialist DSPs for niche campaigns. Publishers, on the other hand, want to be connected to as many sources of demand as possible to not only fill all their ad inventory, but also to achieve the highest CPM for each impression. This difference in incentives largely explains why we have not seen the same extent of industry consolidation on the supply side as we have the demand side.

A recent example of TTD being the primary independent beneficiary of industry consolidation is the June 30, 2023 bankruptcy of MediaMath, a prominent DSP that handled over $590m of ad spend in 2020 and was valued north of $1 billion at one stage[13]. Redburn reports that MediaMath’s largest agency customer, Havas, which likely represented 30% or more of MediaMath’s total spend, transferred 70% of its North American ad spend or just under 30% of its global ad spend on MediaMath to TTD, with the rest substantially all going to Google’s DV360. Assuming the non-Havas budgets shared a similar allocation, this sub-30% capture rate of global spend and 70% capture in North America is significantly higher than TTD’s existing open programmatic share of ~9% and ~16% respectively. This rate of incremental share gain is a strong indicator of TTD’s status as the preferred independent DSP partner for the open web, especially for ad agencies.

One MediaMath former we heard from provided the following anecdote: when he asked a Fortune 50 marketing executive on whether the company would run an RFP for a new DSP following MediaMath’s Chapter 11 filing, the response was “What’s the point? There’s no one out there right now who has global scale like MediaMath did, outside of Google and TTD to an extent.”

In addition to being an industry consolidator, another benefit to scale is the sheer volume of bid requests that TTD’s platform handles. The platform views 13 million queries per second (QPS), which is the number of ad impressions that clients could potentially bid on. This volume of queries is obtained through direct integrations with supply partners and by crawling open exchanges. By viewing more queries than independent competitors, ad buyers using TTD have more opportunities to bid on ad impressions and execute scaled campaigns. And not only does TTD view a huge number of QPS, it is also one of the fastest and most efficient ad buying tools, which matters when auctions take place over milliseconds. Per one Tegus interview with a company former:

“The faster the DSP is at bidding, the more chances it has to win in an auction-based environment…[TTD is] taking billions and billions of queries. So the faster the tool, the more optimization capabilities and all those things together is really what sets them apart…TTD is excellent at optimizing based on efficiency and speed.”

And on why smaller DSPs can’t compete with TTD along this dimension:

“What QPS means is bidding power, bidding power equals engineering, and it also equals data colocation. So the more data centers you have, the more colocation points of presence you have, the bigger the presence, the faster it usually goes and the more you see. So the idea is if I'm at scale on my engineering side and my developers are optimizing the back-end engine or the architecture, and it's set up in a way for me to do that, I can do it faster.”

(As an aside, we note that Index Exchange, an SSP and ad marketplace much smaller than TTD, said it can burst to 10 million QPS on a recent Marketecture podcast[14], so maybe TTD’s QPS is not such a distinction.)

Finally, one consistent piece of feedback we heard from formers and corroborated by our perusal of ad tech forums is that TTD has built a reputation for phenomenal customer service that is second to none. Even though The Trade Desk is a self-service platform, the client success representatives are very hands on from training to campaign management and optimization, almost to the level of a managed service but without the associated cost to the client. This is another advantage that not only scales as TTD captures a greater share of its largest clients’ ad budgets, but is also prohibitively expensive for competitors to replicate as they lack the expense leverage to offer such services on an ongoing basis for free.

2) Independence

Since its founding, TTD has retained an exclusive demand side focus, with management regularly touting the virtues of being independent from the supply side (owning no SSPs or ad inventory) and from conflicted walled gardens. The reasoning is straightforward: ad buyers are the most important participants in the advertising ecosystem because they control the ad budgets, and in the world of digital media where ad inventory is effectively infinite, supply greatly exceeds demand so bargaining power rests in the hands of the buyers.

Management assert that by being the trusted independent DSP, clients trust the platform with their most granular and expressive 1st party customer data that they would never share with the likes of Google or Amazon. This 1st party data can then be leveraged alongside TTD’s 3rd party data integrations to more effectively model and target the most relevant audiences. As Jeff Green explained during the Q2 2023 earnings call:

“As [advertisers] understand more about the power of programmatic, they are choosing the objectivity and performance of our platform over the murkiness of walled gardens more than ever before.”

“Advertisers and media companies are increasingly aware that they need to work with the technology partners who represent their interests, not conflicts of interests. As a result, advertising dollars are shifting to our platform and we will continue to invest in our platform and push the industry to create even more value for advertisers on the open internet.”

This alignment with the advertiser and lack of owned ad inventory also makes for good marketing PR. Within ad tech, the role of the DSP is to source the best inventory at the most efficient CPM for ad buyers, while an SSP’s role is to maximize the inventory yield for the publisher (ad seller). Naturally, these roles serve opposing interests, and any ad tech vendor that owns both demand- and supply-side solutions is subject to a conflict of interest.

At the extreme is Google’s ad tech business, which owns the two largest DSPs in Google Ads and DV360, the largest ad exchange AdX, and the largest SSP and ad server Google Ad Manager (formerly DoubleClick for Publishers). Owning the entire end-to-end stack at Google’s scale allows its DSPs to prioritize Google’s O&O inventory, its AdX to see substantially all auctions and bid prices across the open web before placing its own bids, and its ad server to award impressions to Google bids even if they are not the highest CPM bid.

However, TTD’s dogmatic adherence to independence does have a key downside: it does not own or control any supply and thus can’t tap into inventory at a lower cost for its clients. Part of the theoretical value proposition of an ad tech vendor owning both a DSP and an SSP is the ability to connect ad buyers with publishers at a reduced fee, thus allowing more of an advertiser’s media dollars to reach the pockets of the publisher (and all fees accruing to the single ad tech vendor).

TTD is also entirely dependent on its supply partners making their inventory available to it, though TTD brings significant advertiser demand such that SSPs and independent publishers are unlikely to withhold inventory from TTD if they want to optimize their yield. In fact, the company’s singular focus on the demand side is being increasingly diluted by its push into Supply Path Optimization, which we will discuss later in our analysis.

3) Close relationship with ad agencies

As mentioned in the history section, TTD made the early decision to align with the agency holdcos during a period when agencies were under threat of disintermediation by the rise of programmatic advertising. By getting the agencies onboard early and elevating their relevance in a programmatic world, TTD was able to turbocharge its growth because the agency holdcos controlled so many ad dollars. This agency alignment remains a differentiator for TTD and has helped the company survive competitors that elected to chase advertisers directly and alienated the agencies – e.g. close peer Rocket Fuel’s demise came in part due to trying to circumvent the agencies.

TTD’s agency relationships will be particularly advantageous during the migration of linear TV ad budgets to CTV. The agencies control the linear TV budgets of the largest global and national brands and are likely to continue to do so through the CTV migration. There are two main reasons we believe TTD is in an advantageous position:

Ad agencies are extremely siloed organizations with channel-based media buying teams controlling their own buckets of ad dollars and vying for greater share of their clients’ overall budgets. It is not yet clear whether the linear TV buyers or the programmatic buyers will emerge the primary custodians of CTV dollars, though TTD’s strong relationships at the senior agency and holdco levels should allow it to win regardless; and

Agencies are the “ad whisperers” to their brand clients and need to be convinced of the value of programmatic CTV before they shift their clients’ linear TV budgets into this emerging channel. TTD’s role as trusted partner to the agencies places it in prime position to accelerate the migration of ad budgets to CTV.

However, note that the status quo is changing. Proctor & Gamble, formerly the world’s largest advertiser by ad spend (dethroned by Amazon), began bringing its media activities in-house in 2018, which catalyzed a shift in how brands viewed their agency relationships. This coincided with a push by TTD to build more direct brand relationships through joint business plans (JBP) with large advertisers. Indeed, TTD is a beneficiary of P&G’s in-housing, with P&G’s growing programmatic CTV investments largely being handled by TTD.[15]

We understand that over the last three years, TTD has built out a large client development team that works directly with brand clients, making it easier for brands to control their ad tech stack, their valuable 1st party data, and their media planning decision making process. Today, an estimated 20% of TTD’s gross spend comes directly from brands. Per CEO Jeff Green on the Q2 2022 earnings call:

“Joint business plans, or JBPs, are long-term deals that we sign with leading brands, who aim to increase spend on our platform, often over a multi-year period. In many cases, these agreements are signed with the partnership and cooperation of the agencies that represent the brands. So, as we continue to move upstream and get more direct commitments from CMOs and brand marketers, it not at the expense of our valuable agency relationships.”

We note that Green is careful to couch these JBPs in terms that are neutral to the agencies, but we do not believe this is always the case. One Tegus expert intimated that before TTD agrees to work with a brand directly, it would ask the brand’s (usually former) agency for permission so as to not antagonize the agency. We found this to have a whiff of marketing spin – imagine if your partner or spouse left you for another person, and six months later that person asks for your permission to marry your ex – does that make you feel better towards that person?

Almost every other source we heard from suggested that TTD’s push into direct brand relationships was fraught with risk and needed to be carefully balanced against the agency relationships. This is particularly the case for CTV, where TTD could accelerate the CTV migration by convincing advertisers directly, but this may alienate the agencies in their role as media planning advisors to their clients. As we discuss later in the CTV section, this is perhaps a risk worth taking, as there exists a counter-risk that agencies may be the ones disintermediating TTD in CTV.

4) Greater transparency and control

Management makes a big deal about TTD’s transparency and control – both in terms of decisioning and pricing. Giving control back to ad buyers appears to be a mantra of TTD along with its stance on independence. One of the most common advertiser criticisms of walled gardens is the loss of control – not only over the choice of ad tech (being forced to use the walled gardens’ tools), but also over ad buying decisioning itself. This criticism is becoming more prominent as AI-powered automated “black box” campaigns such as Google Performance Max and Meta Advantage+ wrest all low-level decision-making control away from the ad buyer. These black boxes are also very opaque when it comes to measurement, attribution, and reporting, often leaving advertisers in the dark regarding how their budgets were spent and how the ROAS was achieved.

Per TTD’s 2022 10-K:

“Our platform is transparent and shows our clients their costs of advertising inventory and data, our platform fee and detailed performance metrics on their advertising campaigns. Our clients directly access and execute campaigns on our platform and control all facets of inventory purchasing decisions. Clients also receive detailed, real-time reporting on all their advertising campaigns. By providing transparent information on our platform, we enable our clients to continually compare results and target their budgets toward the most effective advertising inventory, data providers and channels.”

Based on our channel checks, TTD is also one of the most transparent ad tech vendors when it comes to fees. On top of its base platform fee, TTD charges a la carte fees for each value-added feature or data integration that the client turns on. While the company is well known and sometimes criticized for nickel and diming its clients on just about everything on the platform, it at least offers the fee transparency for clients to adjust their use of premium features and data to optimize their TTD invoice against their campaign outcomes. Given some of the damning fee studies conducted in recent years and the general downward pressure on ad tech take rates which we discuss later in the report, this transparency does shield TTD’s take rate somewhat as it can more clearly point to where its incremental fees are adding value to a campaign.

Having said the above, we have seen TTD launch new tools that introduce a layer of opacity to both the decisioning process and fees. For example, Kokai, the next iteration of TTD’s Koa AI that will roll out through 2024, will insert more machine learning throughout the ad buying workflow. Users can turn on real-time ML-driven campaign optimization but this is likely to come at the expense of some level of control and agency. Management couch these optimization capabilities in terms of “recommendations” with the user retaining ultimate control over every ad buying decision, but it should be obvious that no human, especially not TTD’s core user – the recently graduated, overworked and underpaid agency trader handling a dozen campaigns simultaneously – can possibly respond in real time to the optimizations that are being “recommended” by a platform that views 13 million QPS.

Couple the above with the Koa bid shading tool where TTD also optimizes the CPM that is bid for each auction and takes a cut of the purported savings, and Kokai starts to look more and more like Google’s Performance Max or Meta’s Advantage+ campaigns with none of the benefits of their vast pools of 1st party data or O&O inventory to optimize against.

In the remaining two-thirds of this report, for paid subscribers, we discuss our views on:

The CTV and retail media opportunities and why they might not be as exciting as management likes to project;

The sustainability of TTD’s take rate;

The potential impact of 3rd party cookie deprecation; and

Some concluding thoughts on valuation.

Dissecting the growth drivers and other opportunities

One of the main attractions of TTD as a business is its overweight exposure to the fastest-growing channels in digital advertising: CTV and retail media. Management takes every chance to hype up the potential of these opportunities, so in the following sections we will assess each in turn with a rationally skeptical lens. We will also discuss opportunities and implications of Unified ID 2.0 (UID2), TTD’s alternative identifier for advertisers, and supply chain optimization initiatives around OpenPath, ultimately tying back to the key debate around the sustainability of TTD’s take rate.

“These dual forces of retail and CTV are truly bringing the power of data-driven decisioning home for advertisers and it is accelerating their shift to programmatic on our platform.” – Jeff Green, Q2 2023 earnings call.

Connected TV

Connected TV can be broadly defined as video content that is streamed over the internet on connected devices such as smart TVs, over-the-top devices, smartphones, and tablets. There are two revenue models for CTV:

Subscription video on demand (SVOD), where services charge a recurring subscription fee for access to ad-free video content; and

Ad-supported video on demand (AVOD), where ad-supported content is offered for free or at a lower subscription price.

The most prominent SVOD services are Netflix, Disney+ and Amazon Prime Video, and popular AVOD services include Hulu and Peacock. There is a third category of Free Ad-Supported TV (FAST) channels which represent the long tail of typically non-premium content that are available either on demand or linearly, but still fall under an ad-supported model as the name suggests. In the US alone, there are over 1,400 FAST channels amalgamated under providers such as Tubi, Pluto TV and the Roku Channel[16].

For the purposes of this discussion, we focus on the US market as i) US data is most readily available; ii) the US CTV market is most developed; and iii) 87% of TTD’s gross spend in Q3 2023 was in the US. We also refer only to the market for professionally produced content and set aside user generated content platforms such as YouTube and Twitch, as these are not addressable by TTD. YouTube, including YouTube TV, is the largest CTV platform globally ex-China with $29.2 billion of ad revenue in 2022 compared to just $3.1 billion of estimated CTV gross spend on TTD as the largest independent DSP for CTV advertising. However, YouTube ad inventory is only accessible via Google Ads and DV360, Google’s DSP for the open web.

We observe a wide range of CTV ad market estimates, with GroupM being the most conservative and eMarketer having the most aggressive forecasts, though note GroupM excludes YouTube TV while eMarketer and Morgan Stanley both include YouTube TV. Global CTV advertising growth saw a huge spike during the pandemic, supported by the launch of several premium US AVOD services (Peacock, Discovery+, Paramount+ and HBO Max). GroupM’s forecasts look overly conservative considering the recent launch of ad-supported tiers by Netflix, Disney+ and Amazon Prime Video, especially as it also excludes YouTube TV. We see eMarketer and Morgan Stanley’s forecasts as a reasonable range for US CTV ad spend, which is the most important CTV market for TTD.

Source: GroupM (December 2023); eMarketer (October 2023); Morgan Stanley (December 2023); Bristlemoon Capital

Source: GroupM (December 2023); eMarketer (October 2023); Morgan Stanley (December 2023); Bristlemoon Capital

What has driven the rapid growth of CTV since the mid-2010s? The biggest factor contributing to the rise of streaming has been cord cutting by US households, concurrent with the rising adoption of Netflix, Hulu, Prime Video and more recently Disney+ and other network-owned streaming services. This report is a deep dive on TTD so we will spare the details of the decline of linear TV except to say that Netflix’s tenacity and the cable networks’ greed catalyzed a series of irreversible events that have not only reshaped the US media landscape but also the advertising landscape.

Source: Nielsen; Bristlemoon Capital

Source: Morgan Stanley (December 2023)

The decline in linear TV ratings means that broadcast and cable TV advertising no longer has the national reach it once did. Nielsen estimates that total US pay TV viewing hours has declined -65% from 2015 to 2022, compared to a -3% decline in linear TV ad spend according to eMarketer (note this includes both pay TV and broadcast TV). There is simply a shrinking and aging audience to activate multi-million-dollar national ad campaigns against, as 61% of the valuable 18- to 29-year-old cohort have never subscribed to cable or satellite at home before according to a 2021 Pew Research survey[17].

“I said incidentally at the last Investor Day, that traditional television and cable television is a ticking time bomb that we have mistakenly created like 3% declines and that will go on for 20 years. That’s not what’s going to happen. It’s going to get to a place and then fall off a cliff. And it does accelerate as it becomes less and less economically viable. We’re already at that point where it’s accelerated.” – Jeff Green, 2022 Investor Day

Yet linear ad budgets have been slow to migrate, given the decades-long relationships between ad buyers and publishers (TV networks), grandfathered preferential deals at lower-than-market CPMs, and unmeasured entertainment and other kickbacks. Multiple industry experts we heard from indicated shifting budgets from one channel to another was more complex than people realize and can take a long time. Firstly, existing contracts and relationships need to be untangled and sunset. Then, advertisers and their agencies need to test the programmatic channels and form new relationships before they can commit serious ad budgets. Agency linear TV buyers also face career risk– will they be replaced by the programmatic buyers? Fewer humans are required to manage programmatic buying compared to manual directly negotiated orders.

But urgency is building. The fact that linear TV ad spend has declined slower than viewership means CPMs have increased while reach and efficacy of linear TV advertising has declined. At the same time, the cable networks that tried to recreate Netflix’s streaming success have realized 1) producing content exclusively for streaming is expensive, 2) operating a streaming service is expensive, and 3) consumers are only willing to pay so much every month for entertainment. Premium streaming platforms including Netflix have all turned to ad-supported tiers to amortize their content costs over larger audiences and generate incremental ad revenue.

This influx of premium CTV ad inventory from the largest streaming services Netflix, Disney+ (both launched ad-supported tiers in late 2022) and Amazon Prime Video (January 2024) should help accelerate the shift of linear TV budgets to CTV. These services have huge audience reach (albeit likely with substantial subscriber overlap that will need to be managed by a capable DSP), highly engaging content, and are generally considered brand safe with minimal ad fraud compared to UGC platforms and FAST channels. Despite being relatively early days for premium ad-supported streaming, every streaming giant with both an ad-supported tier and an ad-free tier (including Disney, Netflix, Paramount, Warner Brothers Discovery and NBCUniversal) has said that total revenue per user is higher on the ad-supported tier than the ad-free tier[18].

Premium CTV services typically have ad loads in the 4-5 minutes per hour range compared to linear TV ad loads of 15-20 minutes in the US. This combination of attractive channel characteristics and limited ad supply should drive higher CPMs for premium CTV inventory. Indeed, we saw this with Netflix launching its ad-supported tier at $60 negotiated CPMs and Disney+ at $50 CPMs, though both have fallen over the past year as more inventory (growing ad-supported subscriber bases) and weak ad sales (for Netflix at least) have caused their initial premiums to contract. Amazon is expected to launch its ad-supported tier at a more competitive low-to-mid $30s CPM. Even so, these premium CTV CPMs should remain materially higher than average linear TV CPMs in the $10-20 range[19] as demand is likely to exceed supply for the foreseeable future.

Source: eMarketer (September 2023)

Source: OC&C Strategy Consultants

The other reason for higher CTV CPMs, and a key difference to the open web and linear TV, is that substantially all CTV viewers are logged into their service. That is, these are authenticated users with verified emails who can be identified by publishers and advertisers. This compares to just 5% of open internet website users who are typically logged in, according to TTD[20]. We will discuss this further in the Unified ID 2.0 section later, but a logged in user is an identifiable user, and an identifiable user can be targeted by advertisers.

“And with CTV, brands can apply data to their TV campaigns and measure with much more precision, the effectiveness of every ad dollar. And much like retail, advertisers value the authenticated audiences that come with CTV – pretty much every streaming TV viewer is logged in with an email address.” – Jeff Green, Q2 2023 earnings call.

So far, so good – CTV looks to be a tremendous opportunity for TTD and one on which investors can hang a 56x 1-year forward P/E multiple on. In fact, don’t take our word for it; watch this short video of Jeff Green himself promoting TTD’s CTV opportunity during his recent appearance on CNBC’s Squawk Box, before Becky Quick calls him out on his antics.

Jeff Green makes two broad claims about the CTV market in his communications to investors: firstly, he claims the CTV market is perfectly fragmented, with the implicit benefits accruing to the largest demand platform in a fragmented supply environment; and secondly, that all CTV will eventually move to programmatic. Let us assess each of these claims in turn.

“Number two, I would say is, we have to win in CTV, and the good news is, in CTV, that the market around the world is perfectly fragmented.” – Q3 2021 earnings call.

“I don’t think any CTV or broadcast company can form a walled garden strategy in connected television. The landscape is nearly perfectly fragmented where nobody has dominant market share in television.” – 2022 Investor Day.

“As I’ve said before, I believe television is perfectly fragmented for a business like ours.” – Q3 2023 earnings call.

“But it does serve our belief that at end-state all things will be digital and all things digital will be programmatic.” – 2022 Investor Day.

“Every premium video content company from Disney to Paramount to NBCU and Sky, to Netflix have changed pricing and embraced advertising. Not all of them have yet embraced or centered around programmatic advertising, but we predict they will.” – Q3 2023 earnings call.

Is the CTV market perfectly fragmented?

To answer this question, we need to define what “perfectly fragmented” means. Is it “perfectly” fragmented in the economic sense, like “perfect” competition? Clearly not, given the millions of websites on the open internet compared to the dozens of CTV services that generate any kind of meaningful viewership. But is it perfectly fragmented as in just the right amount of fragmentation for a large ad demand platform to take advantage of? That’s the narrative that Jeff Green wants to spin: because the CTV market is not so fragmented as to be unscalable to serve, but also not so concentrated that any one or few services have power, all these large but not dominant publishers need to depend on the advertiser demand that TTD brings.

“This will happen in part because CTV is perfectly fragmented, but collectively huge. It is not so fragmented that you need millions of parties to coordinate, but it’s fragmented enough that no one has enough power to be draconian and do it alone.” – Jeff Green, Q4 2022 earnings call.

We believe this logic may have been sound when TTD first launched its CTV tools in 2016, right up until late 2022 when Disney and Netflix launched their ad-supported tiers. Prior to this, we believe TTD may have been mainly buying impressions on what could be considered “second rate” premium CTV services: the Hulus, Peacocks and Pluto TVs of the world. In fact, up until COVID, TTD may have been largely buying ads on Roku TV, Hulu and FAST channels – we suspect this because the FreeWheel H2 2020 U.S. Video Marketplace Report[21] showed streaming services only had 38% of digital video ad views, and the FreeWheel H1 2022[22] report showed FAST channels still had 29% of ad views and DTC only 13% (both fall under streaming services).

These are mostly publishers who have limited to no capability or incentive to build their own ad tech. In this world, TTD may have gained the impression that its buying power was necessary for these CTV services to maximize their ad yields. But now that the 800lb streaming gorillas have entered the AVOD market, we cannot be so sure that the future will resemble the past.

Source: Redburn

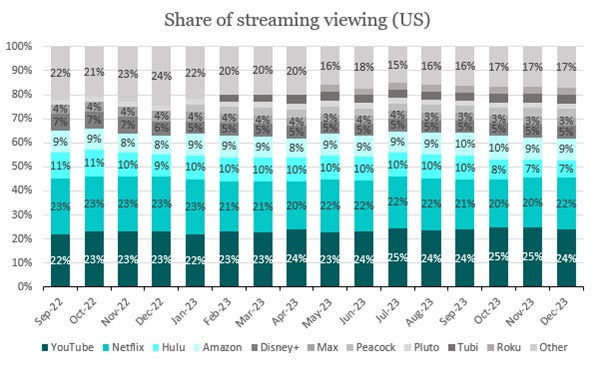

The way we see it, premium CTV is not perfectly fragmented. In fact, we would argue that it is quite concentrated in the hands of a few big publishers. Looking at the Nielsen share of streaming viewing data below, we note the following:

YouTube is a quarter of the CTV market and off limits to TTD (inventory only accessible through Google’s DSPs).

Netflix is the second largest CTV service and is partnered with Microsoft’s Xandr as its exclusive DSP. Yet barely nine months into their relationship, in March 2023, Netflix was reported to be reviewing its ad strategy and considering a build-or-buy pivot away from Xandr[23]. We note that Xandr provides the full ad tech stack to Netflix: ad server, SSP and DSP. It could be that Netflix ultimately decides to in-house the ad server and SSP components (the most important pieces for deciding which ads to run against which viewers) and open up its ad inventory to other 3rd party DSPs, which would include TTD. Alternatively, Netflix could in-house the entire stack and likely will have the scale to force advertisers to buy through an in-house DSP. Even if Netflix does open its ad inventory up to 3rd party DSPs, we would not preclude them from changing their mind and in-housing it later (remember when Netflix said it would never run ads?). There is also precedent of this happening, e.g., when Facebook moved its 1st party data behind its own DSP and effectively killed the 3rd party DSPs buying on the Facebook Exchange back in 2016.

Hulu inventory remains open to 3rd party DSPs, though we understand that some top-flight inventory may be reserved for its own ad buying tools[24]. However, Comcast’s 33% stake is about to be acquired by Disney, who will then own 100% of Hulu. Disney has its own ad server and ad exchange (SSP) that is used for Disney+. While Disney+ inventory is currently available to 30 DSP partners including TTD, we would once again not rule out Disney combining the ad tech stacks of Hulu and Disney+ together and in-housing the DSP function once it has built sufficient scale, data connections and targeting capabilities.

Amazon Prime Video is moving to ad-supported in January 2024 and inventory will be available through Amazon DSP exclusively. It seems unlikely that Amazon would open up Prime Video to 3rd party DSPs and share its incredibly valuable 1st party shopper data.

Disney+, as mentioned above, has its own supply-side ad tech already. It has also integrated Hulu’s DSP, which it has renamed Disney Campaign Manager. It has all the pieces to in-house the full stack should it choose to. Even if inventory remains open to 3rd party DSPs, we believe Disney will aim to minimize ad tech fees by courting direct relationships with brands (which it already has through 100 years of linear TV advertising).

Update: Disney, Fox and Warner Bros Discovery announced last week (February 7) a pioneering sports streaming service that will bundle the sports content of all three networks in one app. The JV will be owned in 1/3rd shares, but let’s be honest – it will be the Disney and friends service. If any content were to entice advertisers to integrate with another DSP, it is sports content. We believe this service may further incentivize Disney to in-house the full ad tech stack, especially if Disney is also responsible for handling ad sales on behalf of Fox and WBD.

Apple TV+, which is not broken out in the data, is likely to in-house its ad tech if it ever launches an ad-supported tier given the company’s philosophy around control and privacy.

Max, Peacock, Pluto TV, Tubi, Roku TV and the long tail of streaming services and FAST channels are unlikely to ever achieve the scale to fully in-house the DSP function, though could potentially reserve some of their “premium” inventory for in-house buying tools. Roku, after acquiring Dataxu (a mid-market DSP), tried to build a quasi-walled garden by fencing its 1st party data behind its in-house DSP. The company eventually had to reverse course after it realized that unlike Facebook, its 1st party data did not have the gravity to pull ad buyers away from the industry leading DSPs such as TTD and DV360.

Source: Nielsen; Bristlemoon Capital

If we sum up the above, there’s:

~55% of CTV viewership (YouTube, Netflix and Amazon) not available to TTD, noting that Netflix could decide to open its inventory to other DSPs, or in-house it after the Xandr partnership expires;

~17% that could eventually be in-housed (Disney+ and Hulu);

Leaving less than 30% of CTV viewership open to TTD (and other 3rd party DSPs) with minimal risk of in-housing.

This doesn’t seem like a perfectly fragmented market to us.

We see two disintermediation risks that TTD faces during the linear to CTV migration:

Walled gardening

Agencies going direct to publishers

We already discussed which streaming services have the scale and/or valuable 1st party data to potentially erect walled gardens, so won’t belabor the point again. We would just add that advertisers and agencies are increasingly consolidating their spend through a single or small handful of DSPs to better track and measure their ad spend across channels and publishers. CTV services will need to carefully balance their desire to minimize or eliminate ad tech fees via in-housing the stack against achieving sufficient auction density to optimize the yield on their inventory. We have not seen any studies analyzing the impact of auction density on yield optimization and would hesitate to speculate on where the drop-off point might be.

On the risk of agencies going direct to publishers, this is likely underappreciated by many. Jeff Green and team spin a compelling narrative about the mutual importance of TTD and the agencies to one another. However, as we discussed earlier, TTD has been expanding its advertiser direct relationships, and it should not be lost on anyone that agencies are doing the same in the opposite direction. Agencies are under increasing pressure from their clients to improve media budget efficacy and minimize fees – basically to justify their existence – and DSPs being the next link in the supply chain are the natural vendors to squeeze.

Agencies are well accustomed to working directly with the handful of national broadcast and cable TV networks that matter in the old world of TV advertising. There is no reason to believe they wouldn’t be equally capable of working with the three or four most important CTV services on direct deals and PG or even PMP campaigns. If the agencies can squeeze or cut out the DSPs’ fees and protect their own thin fees, they will be incentivized to do so.

We believe this is already happening. The most recent development is Publicis’ launch of its CoreAI platform, which has DSP-like functionality and leverages Publicis’ Epsilon 1st party data and ad tech solutions. We learned that during an analyst Q&A, management purportedly confirmed that Publicis absolutely intends to move into the DSP space and squeeze fees out of the channel. Days later, WPP announced its own big bet on AI. While we are not sure if WPP harbors similar ambitions to encroach upon the DSP space, it seems likely the large agency holdcos would follow in Publicis’ footsteps given the highly competitive nature of the industry.

We would also speculate that while US AVOD and FAST ad spend was in the sub-$20 billion range[25] – i.e. before Disney+, Netflix and Amazon’s ad-supported tiers were launched – advertisers and agencies may have been accepting of 3-15% DSP fees (we discuss fees in the next section). But as more and more of the remaining $60 billion-plus linear TV ad spend shifts to CTV – remember, Jeff Green believes linear TV will fall off a cliff – DSP fees start to add up to significant sums. CTV buyers might balk at this fee, particularly as linear TV buying has zero ad tech tax.

There is actually a third disintermediation risk (and opportunity) in the form of supply chain optimization, which we will discuss later in its own section.

What does “shift to programmatic” actually mean?

Even if CTV is perfectly fragmented, what does Jeff Green actually mean when he predicts that all CTV ad buying will shift to programmatic?

We learned in the introduction to programmatic advertising section that there are three main programmatic buying models: Programmatic Guaranteed (we’ll lump preferred deals in here for brevity), Private Marketplaces, and open exchange auctions. While all three are programmatic, they can come at very different CPMs and fees.

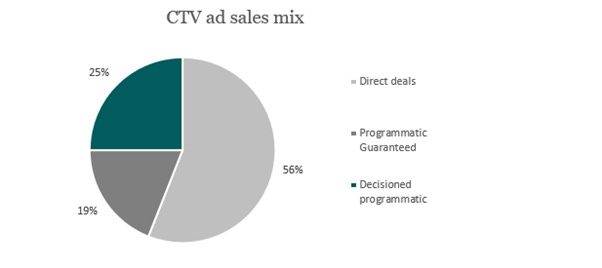

Firstly, let’s establish what percentage of CTV ad buying is currently not programmatic. Data on the share of direct deals in CTV advertising is mixed: FreeWheel, a CTV ad tech platform owned by Comcast, reports that 65% of ad views on its platform in H1 2023 were non-programmatic direct, down from 76% in H1 2021 (i.e., programmatic has been gaining share)[26]; Digiday estimates that direct orders are as high as 70% of CTV ad sales[27]; and TTD showed a chart at its 2022 Investor Day that pinned direct orders at 56% of CTV ad sales, PG at 19% and “decisioned programmatic” at 25%.

Source: The Trade Desk; Bristlemoon Capital