Bristlemoon’s Newest Team Member - Daniel Wu Joining as Portfolio Manager

Thoughts on what risk means to us

It is my great honor to announce that Daniel Wu will be joining Bristlemoon Capital as a Portfolio Manager. Daniel is one of my closest friends. We’ve known each other since 2011 when we met during a university stock picking competition and have been talking about launching a fund together for the past decade.

Daniel and I will be co-managing the Bristlemoon Global Fund portfolio together. An investment partnership is akin to a marriage, and I can think of no one whose judgment, both for investing matters and otherwise, I trust more than Daniel’s. He is one of the sharpest investors I know and conducts himself with the utmost integrity. My desire when launching Bristlemoon was to build a business alongside honorable people who I like, admire and respect. Dan fits the bill, and I am immensely excited about what we will achieve building Bristlemoon together.

Daniel started his career as an Infrastructure Investment Banker at UBS, before transitioning to Goldman Sachs as a banker in the TMT sector. He then joined me at Montaka Global Investments, two and a half years of which were based in New York (we were housemates in both Sydney and New York, so we at least know that we get along!) Most recently, Daniel was a Senior Analyst at Milford. Daniel holds a Bachelor of Commerce and Bachelor of Laws from the University of Sydney.

In addition to his analytical capabilities, Dan is also a fantastic writer and will be regularly contributing to the Bristlemoon newsletter. It is worth hearing from Daniel in his own words. Below, he has penned a piece on the topic of risk that I’m sure you will find most interesting. It is also worth following Daniel on X (Twitter), where he will be posting his thoughts and insights.

What does risk mean to us?

When I made the decision to leave a secure, well-paying job to join George in building Bristlemoon, concern was expressed to me by some family members and friends that I was making a risky career move. Having known George for 14 years and understanding our aligned philosophies and very complementary skill sets, I did not see the move as exceedingly risky from a career or financial perspective. The feedback did, however, prompt me to reflect on how we contemplate and manage risk at Bristlemoon.

We are partial to Howard Marks’ favored definition of risk, which is a quote from Elroy Dimson of the London Business School: “Risk means more things can happen than will happen.” Higher risk does not invariably produce higher returns, but rather a wider distribution of possible outcomes. This definition is often accompanied by a risk/return visualization to demonstrate the widening range of possible outcomes as one moves out along the risk spectrum.

Source: Oaktree Capital Management, L.P.

We would note that the gradient of the risk/reward line typically slopes up and to the right because as one moves out on the risk spectrum, the maximum loss is -100% (unless leverage is involved) while the maximum gain is unlimited. This is essentially why venture capital works – with a large enough sample (or portfolio) size, the few uncapped winners should more than offset the many losers. But any single investment on the far right of the risk spectrum is unlikely to produce a winner commensurate with the risk taken. Hence it is instructive to redraw the chart to reflect return on a dollar basis as follows.

Source: Bristlemoon Capital

We also like this definition of risk as it highlights the not-so-intuitive relationship between uncertainty and payoff. Uncertainty arises when more things can happen than will happen. It falls upon the investor to manage this uncertainty through a combination of careful stock selection, portfolio construction, and hedging if required. (More on payoff later).

Stock selection amidst uncertainty

Because a) we don’t know what we don’t know, and b) the future is inherently uncertain, we believe the best way to manage this uncertainty during the stock selection process is to try and shorten the list of knowable adverse things that can happen. We think about these “things that can happen” in three buckets:

things in our control;

things in management’s control; and

things outside of management’s control.

Things in our control

Things in our control mainly relate to whether we as analysts have done sufficient research and analysis into a given investment opportunity. If an investment blows up because of something in our control, we simply haven’t done adequate due diligence. Even a simple checklist of questions (not exhaustive) can help reduce the likelihood of being blindsided by something obvious:

Have we asked the right/pertinent questions?

Have we pursued all available avenues of enquiry?

Are our assumptions reasonable – i.e., do they reflect the world as it is or a version of the world as we want it to be?

What are other investors thinking or expecting?

Have we considered how we could be wrong?

Have we checked our biases?

Is the business or investment understandable, and do we truly understand it?

Things in management’s control

Things within management’s control tend to be stock-dependent but typically relate to strategy and execution. For example, if we are analyzing a turnaround situation, considerations pertinent to the success of the turnaround may include product improvements, competitive response, cost controls and corporate culture. The more of these factors that are within management’s control, the more confidence we can have in the company’s ability to respond to headwinds and tailwinds as they arise.

Note that not all management teams are equal. Founder-CEOs like Mark Zuckerberg or Jensen Huang typically have much more control over execution and especially strategic direction compared to professional outside management teams installed by a Board of Directors.

Things outside of management’s control

Finally, things outside of management’s control may include certain adverse regulatory and geopolitical developments, or other external black swan events. Or it could be as simple as operating in an industry that is known to have unfavorable industry dynamics. As Warren Buffett says, “When a manager with a reputation for brilliance tackles a business with a reputation for bad economics, the reputation of the business remains intact.” Frameworks such as Porter’s Five Forces or Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers can be helpful in assessing whether management have more or less control over the range of possible outcomes.

All of this ultimately feeds into conviction, which George has written about in our Q4 letter and his article on conviction so we won’t repeat here. The fewer unanswered questions that we have and the shorter the list of unmitigable possible adverse events, the stronger the conviction we can build in an investment idea.

What about payoff?

The more mathematically minded readers might be thinking: if more things can happen than will happen, surely we can quantify this risk as an expected value and rank potential investments by their expected values. In statistics, expected value is the mean of the value of each possible outcome weighted by the probability of those outcomes. In practice, only one outcome will happen at any given time.

For example, just as the weather can’t be both 70% raining and 30% clear when the forecast probability of rain is 70%, TikTok can’t be both 67% banned and 33% not banned at the same time (Polymarket odds on January 13th). META’s recent share price performance reflects the rising probability of a TikTok ban, but it would be erroneous to conclude that META at $616 per share is reflecting an outcome where TikTok is only 67% banned. This is the not-so-intuitive relationship between uncertainty and payoff.

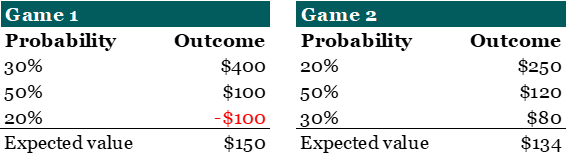

We believe it can be dangerous to think in terms of expected values because a point estimate based on probabilities belies the range of potential outcomes it is derived from. Consider the following games of chance that cost $100 to play:

Which game would you rather play? Game 1 has the higher expected value, so without knowledge of the underlying outcomes, you might choose to play Game 1. But Game 1 also has 20% chance of losing all your money. With this knowledge, you might choose to play Game 2 instead even though the expected value is lower. Or perhaps you are willing to play Game 1 over Game 2 for $100 or even $1,000, but not for $100,000 or $1 million.

As illustrated in this example, if the left tail of things that can happen is a catastrophic loss, that loss needs to be taken into consideration during stock selection or position sizing irrespective of the right tail upside.

In a similar vein, we also despise the use of point estimate valuations for the same reason. Saying a stock trading at $100 is worth $126 thus offering 26% upside conveys far less useful information than framing the investment as producing an estimated 60% probability of being worth $120, 20% probability of being worth $70 and 20% probability of doubling your money.

Managing uncertainty through portfolio construction

Try as we might, we can never reduce the distribution of possible future outcomes to a single outcome – implying certainty – nor can more than one possible outcome transpire at any given time. But what we can do is mitigate the remaining uncertainty post-stock selection via portfolio construction.

Ideally, a portfolio of stocks should be resilient to changes in market conditions, but resilience across a range of environments necessitates suboptimal performance in any given environment. While we appreciate the rationale for building sector- and factor-neutral portfolios that distill stock selection alpha, we believe active portfolio management – e.g., when to lean into a sector or theme and when to rotate out – can be a material contributor to alpha when performed well.

Thus, we aim to construct a portfolio consisting of our highest conviction ideas while minimizing the overlap of known adverse outcomes that can happen. Our Q4 letter covers our position sizing framework in depth but one element we would like to expand upon here is the use of what we call risk budgets. These are soft limits on what we are comfortable losing on specific categories of possible future adverse outcomes, such as the failure of China fiscal stimulus to boost consumption demand in 2025, a sharp deceleration in AI infrastructure investment, or even total portfolio exposure to stocks with a history of large post-earnings moves (particularly declines). They are weighed against the upside from possible future positive outcomes and help inform our position sizing decisions.

It may seem redundant to deconstruct the sources of potential loss at the portfolio level in this manner. After all, isn’t it more straightforward to categorize a portfolio top-down into broad thematic buckets and monitor exposures that way? While the latter approach is indeed more straightforward, a stylized example may help illustrate the nuance that gets lost.

Let’s pretend we own Nvidia, Microsoft, SK Hynix and AppLovin (amongst other stocks). These four stocks ostensibly fall into the “AI winners” thematic bucket, but by our assessment the range of adverse outcomes that can lead to loss have limited overlap. Nvidia and SK Hynix are most exposed to a pause or unwind of AI infrastructure capex, and SK Hynix faces the additional risk of memory industry overcapacity. On the other hand, Microsoft announcing that it will spend $70 billion on data center capex in CY 2025 instead of the expected $80 billion might be a source of upside if the capex reduction is due to model efficiency gains. For AppLovin, the key adverse outcome is a slow ramp of its expansion into e-commerce advertising that fails to match very elevated expectations; an unwind of AI infrastructure capex is unlikely to have any direct impact on AppLovin’s share price. Of course, this stylized example ignores other factors that may contribute to positive correlation such as size and/or momentum.

It should be noted that these soft risk budgets do not apply to all of our long positions. The focus is on the largest or most volatile positions that can hurt returns the most. For our shorts, we have a separate, strict risk management framework that is discussed here.

Finally, when investors think about risk, their mind often turns to the risk of loss or other negative outcomes. Our preferred definition of risk simply denotes a wider distribution of possible outcomes, both negative and positive. This helps us frame discussions about risk in a more neutral manner that doesn’t foreclose on the consideration of potential things that can go right.

Disclaimer / Disclosures

The information contained in this article is not investment advice and is intended only for wholesale investors. All posts by Bristlemoon Capital are for informational purposes only. This article has been prepared without taking into account your particular circumstances, nor your investment objectives and needs. This article does not constitute personal investment advice and you should not rely on it as such. This document does not contain all of the information that may be required to evaluate an investment in any of the securities featured in the document. We recommend that you obtain independent financial advice before you make investment decisions.

Forward-looking statements are based on current information available to the author, expectations, estimates, projections and assumptions as to future matters. Forward-looking statements are subject to risks, uncertainties and other known and unknown factors and variables, which may affect the accuracy of any forward-looking statement. No guarantee is made in relation to future performance, results or other events.

We make no representation and give no warranties regarding the accuracy, reliability, completeness or suitability of the information contained in this document. To the maximum extent permitted by law, we do not have any liability for any loss or damage suffered or incurred by any person in connection with this document.

Bristlemoon Capital Pty Ltd (ABN: 22 668 652 926) is an Australian Financial Services Licensee (AFSL Number: 552045).

George Hadjia is associated with Bristlemoon Capital Pty Ltd. Bristlemoon Capital may invest in securities featured in this newsletter from time to time.

Nice one.