Thoughts on Hemnet and Rates of Change

Why pulling the pricing lever too fast is risky

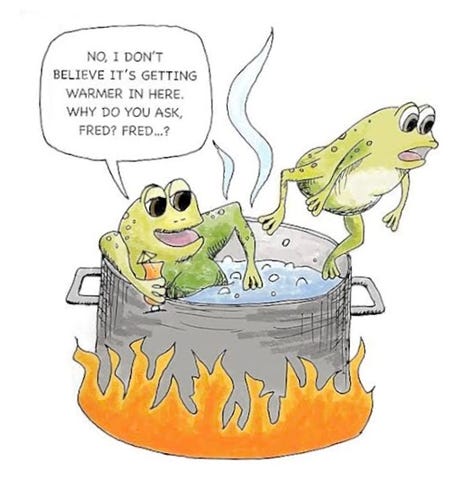

You’ve probably heard of the boiling frog analogy (or myth[1]). The idea is that if a frog is suddenly put into boiling water, it will jump out; but if it’s put in tepid water that’s boiled slowly, the frog will fail to perceive the danger and boil to its death.

Source: Novi

While a somewhat trite and erroneous analogy, it vividly captures the concept of creeping normalcy: the phenomenon where significant changes are accepted as normal when they occur gradually, through a series of small, often unnoticeable, increments of change. This idea around the importance of the rate of change in shaping the end outcome is one that investors should deeply reflect on. It is an idea that is pertinent to the pricing decisions of companies, particularly those with genuine pricing power.

Pricing power is great. If you’re an investor, you want the businesses you’re invested in to have pricing power. However, the speed at which a company seeks to extract value from its customer base via price increases matters – a lot. This is because the speed at which a company raises prices can directly affect the ultimate price level that can be achieved.

Essentially the human mind needs time to habituate to change. So, if a company raises prices too quickly, it interferes with our ability to incorporate these higher prices into a new normal.

Jared Diamond, who coined the term creeping normalcy in his book Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed, also introduced a related concept called “landscape amnesia”: the idea that people forget what the surrounding landscape looked like 50 years ago because the year-to-year change has been so gradual.

This concept of landscape amnesia is why there are examples of companies increasing prices by many multiples over time. People continue purchasing those companies’ products or services, with minimal fuss, because the gradual nature of those price increases afforded them time to mentally adjust, relegating the formerly lower prices to a distant, forgotten memory.

Think about the health insurance premiums charged by UnitedHealthcare (the average health insurance premium has outpaced inflation for almost all of the past 25 years, but seldom by more than a double-digit percentage point spread). Or the price per pound for a box of See’s Candies (which has increased by around 5% per annum for more than 50 years). These price increases have been relatively gradual, occurring over the span of decades.

Thought of another way, a necessary precondition for a high level of pricing-led value extraction is for those price increases to be gradual. Pull the pricing lever too aggressively and you risk upsetting your customers, and occasionally the general public and regulators.

Risks from pulling the pricing lever too hard

A rather extreme and morally reprehensible example of rapid price increases involved Daraprim, a 62-year old drug which is used to treat life-threatening parasitic infections. Turing Pharmaceuticals, run by a controversial fellow named Martin Shkreli, acquired the Daraprim drug and overnight raised the price from $13.50 a tablet to $750 (a 5,456% increase for those counting).

While Shkreli was sentenced to prison for an unrelated securities fraud matter, a U.S. federal judge later ruled that Shkreli violated antitrust laws via actions that sought to monopolize the market for Daraprim (and thus enable Turing to continue charging exorbitant prices for the drug).

Martin Shkreli was banned for life from the pharmaceutical industry, an ignominious end to one of the most egregious spectacles of price gouging in recent history. It turns out that raising prices by 5,000%+ in one fell swoop is not a sustainable strategy for value generation!

There are other examples of companies dramatically raising prices in a short span of time (although not in a nefarious way like the Daraprim example). The consequence of these speedy price hikes is similar: they can jeopardize the company’s ability to raise prices in the future.

FICO is an interesting, and topical, example of this dynamic, with the company having put through gargantuan price increases over the last seven years. Importantly, these price increases were from a miniscule base, and after decades of precisely zero price increases.

Incredibly, the royalty rates that FICO received from the consumer reporting agencies (CRAs) remained virtually unchanged for nearly 30 years after the FICO score was first introduced in 1989. After a multi-year renegotiation of its license agreements with each CRA that began in 2012, FICO put through its first increase in the royalty rate in 2018. At that point it was charging around 50-60 cents per score for mortgage lenders.

Investors salivated over the latent pricing power. And FICO certainly did its best to extract it. More recently, FICO put through its fourth major price increase: in October of 2024, FICO notified its credit bureau customers that in 2025 the company’s wholesale royalty will increase to $4.95 per score for mortgage originations (a 41% increase over the 2024 wholesale price for mortgage lenders of approximately $3.50 per FICO Score).

Objectively, $4.95 does not appear to be an extortionate amount. In fact, it comprises an infinitesimal cost within the mortgage value chain. Consider that the $4.95 per score royalty comprises on average 15% of the $80 to $100 tri-merge bundle cost – that is, a single report which combines credit information from the three national credit bureaus. Furthermore, FICO comprises just two-tenths of one percent of the total average mortgage closing costs of $6,000. It would be a long bow to draw to argue that a 0.2% cost amounts to an impediment to home ownership in the U.S.

However, regardless of the rationale or fairness of these price increases, FICO has still raised prices for its FICO Score by almost 900% since 2018. This has caused regulatory consternation.

The large and rapid price increases enacted by FICO are likely a major reason behind the recent rumblings of Bill Pulte, Director of the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), who has threatened imminent regulation to reign in FICO’s pricing power.

If FICO had instead raised prices gradually over multiple decades, no one would have kicked up a fuss about its current pricing. We would bet that no one would have protested if FICO’s prices were demonstrably higher than they are today, so long as FICO’s price taking had been gradual. The lesson from this is it’s perhaps best not to play catchup and make up for lost time when it comes to price increases!

The ultimate prices a business is capable of charging are path dependent: raise prices too quickly and you risk people taking issue with that value extraction. This is especially so if you are a monopolist and customers have no viable alternative.

Thoughts on Hemnet

With this background around pricing increases and rates of change, it is worth now turning our attention to Hemnet Group AB, an investment held in the Bristlemoon Global Fund and one that we wrote about in our March 2025 quarterly letter.

Let’s start with some context. Hemnet has raised prices aggressively in recent years. The average revenue per listing (ARPL) has increased by 4.5x in the last five years, going from SEK 1,414 in FY19 to SEK 6,383 in FY24. Over the last nine years, the ARPL has increased by a whopping 13.1x. While some of that growth reflects product mix – property sellers opting into higher-priced listing packages – the company has still put through material like-for-like price increases.

Investors with a penchant for quality businesses get starry-eyed at this sort of pricing power – successfully raising your prices on customers is one of the clearest indications of a business moat.

However, there’s a dichotomy that results from pulling the pricing lever too hard. On the one hand, investors in the stock benefit immensely from this sort of growth and the associated high incremental margins; often this causes these types of businesses to trade at rich earnings multiples. On the other hand, customers on the receiving end of these price increases can grow increasingly frustrated and resentful at the increasing value extraction, particularly when the pace of value extraction is rapid.

Unfettered pricing power doesn’t exist: every pricing-led growth strategy has a breaking point where those prices will be extreme enough to prompt user churn, or egregious enough to draw the ire of regulators who can issue fines, or worse still, regulate future price increases. The trick is making an accurate assessment of where that breaking point is. We do not think that Hemnet has reached this breaking point, but we will discuss some of the issues that have resulted from the historically speedy ARPL growth.

There have been some recent developments in Sweden that have muddied the narrative for Hemnet and its pricing-led growth story, namely around: 1) regulatory risk; and 2) competition.

Regulatory scrutiny?

In late May 2025, an article published in Affärsvärlden flagged concerns about Hemnet’s agent compensation structure as well as the fairness of its listing fees. There were comments in the article from the Swedish Estate Agents Inspectorate (FMI) around agents being incentivized, via higher remuneration from Hemnet, to recommend more expensive advertising options on Hemnet to property sellers, and that they would assess if this was a violation of the Estate Agents Act.

We are not concerned about this. The FMI has no jurisdiction over Hemnet, only on the actions of real estate agents in Sweden. Any changes over what Hemnet can pay real estate agents in Sweden would likely also be a boon for Hemnet’s margins – in this scenario they would not need to pay away as much of their revenue to real estate agents.

We did have some concern, however, over comments in the Affärsvärlden article from Martin Mandorff, the Head of Market Abuse Unit at the Swedish Competition Authority (SCA). The reporter asked Mandorff a number of hypothetical questions, so we would note that his comments, without the relevant context of that hypothetical question, do appear much more alarming than otherwise. Mandorff made the follow comments to Affärsvärlden for the article (translated from Swedish):

“During the spring, we have noticed that the issue has grown with the new price models. We are constantly considering whether there is anything that we should investigate with our tools.”

“It is clear that this market is not opening up and that pricing has skyrocketed. This makes us more concerned now.”

“Based on the Competition Act and the abuse rule, you may find that a company has contract terms or pricing that excludes other players. Prices can also be too high, although this is more unusual. In that case, we can order the company to stop doing so. There is also the possibility of a competition fine if you have harmed competition…However, overpricing can constitute an abuse.”

“Then it becomes more a question of whether we see indications that there is pricing that seems so high, that given the cost structure of the industry, it is simply no longer reasonable. I don't want to speculate on when that will happen.”

Let’s be clear – an official at the regulatory body going on record making these sorts of comments is in no way a positive for Hemnet. Fears around regulatory risk were no doubt exacerbated given this article was hot off the heels of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) announcing that it was investigating the pricing practices of REA Group, owner of the Australian property portal realestate.com.au.

We suspect Mandorff’s comments are simply a shot across the bow from the Swedish regulator, and do not signal imminent regulatory intervention, but we also cannot brush these risks aside completely.

The problem with regulatory risk is that 1) it’s difficult to handicap the likelihood that it transpires; and 2) it can lead to outsized negative outcomes. The presence of so-called stroke-of-a-pen risk for an investment simply makes it harder to underwrite a set of future value outcomes with confidence. It’s just hard knowing what the business might look like in the future if an external party can step in and begin interfering with how the company conducts its affairs.

It is difficult to know whether Mandorff’s public comments indicate an actual investigation from the SCA is forthcoming. Perhaps the more subtle risk is that these comments may have a diminutive impact on future price increases, surreptitiously curtailing the level of pricing power the company is capable of exerting over property sellers due to fear of a regulatory crackdown. We don’t know but will get answers in future quarters when we see the degree to which Hemnet adjusts the prices of its listing packages.

We would make a few points that support Hemnet’s listing fees:

A property is in all likelihood the seller’s largest asset. These assets are transacted infrequently, and chances are the seller doesn’t even recall how much they paid Hemnet to advertise any past properties they’ve sold. We believe that the cost for advertising on Hemnet to show your property to the largest audience in Sweden is miniscule. For example, an SEK 7 million (c.$730,000) property in Stockholm would cost SEK 7,950 (c.$830) to advertise on the Basic starter package. Expressed another way, it costs just 11 basis points of the home’s value to list your property on Hemnet, on the least expensive tier.

Property sellers opt in to higher priced packages. Their choice is voluntary. Typically, they will upgrade because of priority placement and more views per listing. In other words, they’re paying more for the premium listing packages on Hemnet because they’re getting more value. For example, the company recently disclosed that Hemnet’s Max listing tier receives 88% more views per listing than the average Basic ad[2].

Using the Stockholm property example above, it costs SEK 26,150 for a property seller to purchase the Hemnet Max package (the most expensive option), which equates to roughly $2,700. This is around 37 basis points of the value of the property. Is this worth it? All it would require is for the extra exposure you get from the Max listing resulting in an additional buyer who is willing to pay $2,700 more for the property. This, to us, does not seem inconceivable. If the Max listing leads to an additional interested party who offers just 1% above the SEK 7 million asking price (i.e., an extra SEK 70,000), then this results in a 3.8x return on investment on upgrading to Max (i.e., the additional SEK 70,000 of property value realized compared to the incremental SEK 18,200 it cost to upgrade from the Basic package to Max for that Stockholm property).

The worsening of the narrative around Hemnet has also been driven by fears of increasing competition, a somewhat surprising fear given history has shown it to be incredibly difficult to assail the leading property portal in a market.

Competition heating up?

More recently, the narrative has gained traction that Hemnet’s aggressive pricing has inadvertently opened the door for competition, namely Booli. Booli, which has been around since 2007, is a property portal owned by SBAB, a Swedish bank. It’s free to list on Booli. The way it works is that agents will list a seller’s property on their own real estate website. Booli then “scrapes” this listing data from the real estate agent’s website. This results in Booli having a holistic view of the listings landscape, and there are listings that appear on Booli which are not on Hemnet.

Booli gained a foothold in Sweden via its free property valuation tool (reminiscent of Zillow’s “Zestimate” feature, which served as the initial wedge for the company to get early traction in the U.S.). People are curious to know what their property is worth, and Booli has racked up 800,000 registered homeowners that it sends property valuation updates to on a weekly or monthly basis.

Traditionally people have gone to Booli to get updates on the value of their property and how neighboring valuations are trending. To some extent more recently, people are going to Booli to look for a property to purchase.

The primary reason why we have been unconcerned with Booli is because listing dollars follow eyeballs, and most of the eyeballs are on Hemnet. For example, Hemnet receives 16x the number of clicks on listings compared to Booli. However, there is data to suggest that Booli has been gaining traffic share, narrowing the gap between itself and Hemnet.

Let’s take a look at app downloads for the two property portals (app users for portals tend to be stickier, higher quality users). If we were to look at Sensor Tower data for app downloads, there appears to be a wide divergence between Booli’s cumulative app downloads and MAUs. The MAU line is so small you can barely register it off of the x axis of the graph. Note that for both the Booli and Hemnet charts below, the cumulative downloads are only starting in January 2017 because that is where our Sensor Tower dataset begins, not because this is when the Booli and Hemnet apps were first introduced.

Source: Bristlemoon Capital; Sensor Tower

This enormous delta between cumulative downloads and MAUs potentially signals that many of the Booli app downloads fail to convert to regular users of the app. This could be due to a poor user experience, or some other reason. The data does look strange to us. Hemnet’s graph, on the other hand, looks much more like what you’d expect from a healthy app, with a more normal ratio between MAUs and cumulative downloads.

Source: Bristlemoon Capital; Sensor Tower

We would further note that Hemnet is currently maintaining a 69x MAU lead over Booli, and despite Booli gaining traffic share and having solid download activity, Hemnet has still grown its ARPL by around 6.8x since 2017 (a 31.4% CAGR over this seven year period).

So why has Booli been gaining traffic share in recent years?

Pre-market listings

It is worth now turning our attention to what is known as the pre-market for listings in Sweden. These are properties that are being prepared to be sold, but are not officially for sale. Think of it as a “Coming Soon” section for properties that are yet to officially list for sale.

Basically, the property gets listed on a real estate agent’s website, and then Booli scrapes that data. For this reason, Booli has more listings than Hemnet – Booli includes all the pre-market listings that appear on the agents’ websites. The trade off of Booli scraping listings, as opposed to agents directly uploading those listings like what happens on Hemnet, is that a portion of the listings on Booli are stale (i.e., incorrect, out-of-date information about the listing, or even where the property is no longer for sale). The lower information quality for listings on Booli feeds into a lower quality user experience (which could explain the abovementioned poor MAU retention data).

The pre-market in Sweden gained prominence during the very hot property market during the pandemic. A listing could be shown in the pre-market with minimal preparation, and buyers would find that listing and make offers for that property. Around the pandemic, the listing days on Hemnet were around two weeks, meaning that a property would transact just two weeks after listing on the site. As of Q1 of 2025, listing days on Hemnet have blown out to 47 days. In other words, it’s a much slower market where it’s harder to find buyers.

Logically, one would think that in a slower market there’s an even greater impetus for property sellers to advertise on Hemnet. This would result in more eyeballs, and thus a higher chance of that property transacting. However, there are nuances in the Swedish market that appear to have derailed this dynamic.

For example, the slower market has made it more competitive amongst real estate agents in Sweden. Some are running on fumes, struggling to eke out commissions given the much smaller volume of properties that are transacting. We have heard instances of agents lowering their commission rates to entice the property seller to choose them as their representative agent.

One lead generation tactic used is for agents to tell a property seller that they can potentially save them money by first listing the property on that agent’s website as a pre-market listing. Booli will scrape this listing and there’s a chance that somebody sees the property and lobs in an offer. If the property doesn’t transact on Booli, then the agent will recommend listing on Hemnet.

This tactic lowers the friction and risk for property sellers – it’s free, after all. It also creates optionality for agents in the off chance that somebody does make an offer for the property. The key question is what portion of these Booli listings ultimately end up on Hemnet due to an inability of Booli to surface a buyer. Our view is that these are lower quality listings, some portion of which are uncommitted sellers who are hoping for a good buy offer that meets the price they’re hoping for.

We believe that the sensible move for property sellers is to always list on Hemnet in order to maximize the number of views per listing. However, while Hemnet pays agents a commission (which in theory should incentivize them to recommend sellers to list on Hemnet), the competitive nature of the Swedish property market for agents creates a binary proposition. Agents either contract with the seller so that they’re the representative agent on the listing and receive a commission for selling the property (even if it’s a smaller amount due to a lower sale price), or they don’t secure the listing and thus get nothing.

Notably, agents in Sweden typically do not get a salary but rather their pay is entirely commission based, exacerbating this dynamic. The Hemnet commission, while nice, pales in comparison to the commission that an agent gets from the property seller when the property sells. This is especially so, given that in many cases the commission paid by Hemnet is retained by the real estate brokerage, not the individual agent, and is used to fund things like Christmas parties and company vacations.

It is also worth mentioning that in a slower real estate market, sellers are reluctant for their property to remain unsold on Hemnet for too long. If this happens, potential buyers might interpret a long listing duration as there being something wrong with the property which could turn them off making an offer.

We think that a risk for Hemnet is if the market remains weak, then the pre-market might continue to gain traction which helps Booli increase its share of traffic. To us, this pre-market dynamic is a symptom of a paucity of seller leads for agents. We believe that Hemnet should be able to address this if it were to introduce a seller lead generation tool for agents. Responding to Booli directly, in our view, would be strategically challenging for Hemnet.

The fact that listings can appear on Booli for free makes it difficult for Hemnet, which subsists off of a paid listings model, to mount an effective response. Booli does not charge for listings. Rather, the site serves as a mortgage lead generation funnel for its bank parent company, SBAB. There’s an element of counter-positioning here. Hemnet will no doubt be reluctant to mimic Booli’s free pre-market listing stance due to the damage it would cause to its paid listings. We have seen Hemnet respond to Booli by introducing a Coming Soon tab, but sellers must pay to list their properties here (unlike Booli). Instead, we believe that Hemnet needs to better demonstrate the value that its platform offers to sellers, which might require an increase in marketing spend, as well as introducing better lead generation functionality for agents (as mentioned above).

Much of the above might also be resolved if the Swedish property market were to tighten, which would likely result from the Riksbank (Sweden’s central bank) cutting rates. However, there’s maybe another wrinkle in this scenario.

The slower Swedish property market has almost certainly been a factor in driving a high upgrade rate to the Premium listing tier. The Premium listing tier had historically been the exclusive tier with the unlimited renewal feature (the recently introduced Max tier now also includes unlimited renewals). What this means is that the property listing can be renewed every 30 days at no additional cost (versus the Base and Plus packages where you need to pay an additional cost to maintain your listing after 30 days).

Given the slower market, with listing days extending to 47 days, unlimited renewals has become the killer feature of Premium and Max. The problem is that if the market were to tighten and listings transact in a sub-30 day time frame, then the benefit of having a perpetual listing for a one-off cost enormously diminishes. We suspect this would be a negative for upgrade activity to Premium and Max, but note that Hemnet can always rejig the pricing of its other packages to steer users towards these more premium listing tiers.

Conclusion

Let’s be clear: our Hemnet thesis has not played out as expected. The company was once the Fund’s largest position, and we were too bullish on the ability of Hemnet to extract value via price increases, as well as the speed at which sellers would upgrade to the new Max tier.

We suspect that the introduction of Max (which was rolled out earlier than initially scheduled) was a consequence of a faster-than-expected upgrade rate to Plus and Premium. Essentially, the change to the agent commission model on 1 July 2024 drove very strong upgrade rates to Plus and Premium, which turbocharged the company’s growth but also forced the need for a new listings tier (so that sellers could better differentiate themselves via the more expensive Max tier).

It's possible that the strong upgrade rate following the agent commission changes caught Hemnet’s management team off guard, creating fears around the ability to sustain this heady growth, as well as the difficulty in managing investor expectations. The problem with such a robust upgrade rate, and the resulting strong ARPL growth, is that you are pulling forward growth from the future, potentially creating a growth air pocket. Growth air pockets usually aren’t good for stock prices. It’s likely that Hemnet is now trying to manage the company to a lower, but more consistent growth path. This has been problematic for the stock to the extent that most investors, including us, were expecting very strong ARPL growth in FY25, which might now be less likely.

Our enthusiasm towards pricing-led growth strategies has cooled, particularly if the pace of price increases has been rapid, and the company is well into their journey of hiking prices. This is because pricing-led growth is inherently lazy if there is no accompanying uplift in value to the end user. Contrast this with a company like NVIDIA which is rapidly innovating, such that new GPUs are released at far higher prices than previous generations, but there is an enormous performance benefit that justifies that price increase. Customers are far less likely to balk at price increases if there is a commensurate uplift in the value that the company’s product or service.

Investing teaches many lessons – but one stands out: the speed at which a company raises its prices will ultimately determine the sustainability of that company’s pricing power.

Disclaimer / Disclosures

The information contained in this article is not investment advice and is intended only for wholesale investors. All posts by Bristlemoon Capital are for informational purposes only. This article has been prepared without taking into account your particular circumstances, nor your investment objectives and needs. This article does not constitute personal investment advice and you should not rely on it as such. This document does not contain all of the information that may be required to evaluate an investment in any of the securities featured in the document. We recommend that you obtain independent financial advice before you make investment decisions.

Forward-looking statements are based on current information available to the author, expectations, estimates, projections and assumptions as to future matters. Forward-looking statements are subject to risks, uncertainties and other known and unknown factors and variables, which may affect the accuracy of any forward-looking statement. No guarantee is made in relation to future performance, results or other events.

We make no representation and give no warranties regarding the accuracy, reliability, completeness or suitability of the information contained in this document. To the maximum extent permitted by law, we do not have any liability for any loss or damage suffered or incurred by any person in connection with this document.

Bristlemoon Capital Pty Ltd (ABN: 22 668 652 926) is an Australian Financial Services Licensee (AFSL Number: 552045).

George Hadjia and Daniel Wu are associated with Bristlemoon Capital Pty Ltd. Bristlemoon Capital may invest in securities featured in this newsletter from time to time.

[1] https://www.abc.net.au/science/articles/2010/12/07/3085614.htm

[2] https://efn.se/hemnets-svar-efter-kritiken-ska-absolut-tas-pa-allvar

Finally coming around to NVDA!

sometimes you can get away with it (eg Transdigm buying up airplane parts manufacturers and raising prices 10x). it helps a lot to be far away from the public eye